|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

By Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development (ZIMCODD)

- Introduction

The March Policy Digest examines the Health Service Amendment Bill (HSAB) from a social and economic justice perspective. It seeks to determine if the Bill promotes health equity as well as value social and economic justice for all citizens. According to the government, the bill seeks to align the Health Service Act to the Constitution. This will be attained by designating the Health Service as a Commission and providing for the functions of such a commission. The Bill aslo discusses the parameters of collective job action by the Health Service personnel. To this end, this digest will determine if the amendments being promoted by the government will ensure the rights and interests of both the patient and the employee.

2. Context

Health is a fundamental human right according to section 76 of the Zimbabwean Constitution, hence the overall outcome of the Health sector during the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS1) Period (2021- 2025) is to improve the quality of life, and increase the life expectancy at birth from the current 61 years to 65 years. Good health is essential to sustainable development and Zimbabwe has made significant progress in the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) underpinned by the NDS1 and the country’s Vision 2030 which mainstreams the Global 2030 Agenda to facilitate joint implementation for improved health outcomes.

The Government of Zimbabwe through various policies and programmes is working to achieve universal health coverage through sustained investment in public health infrastructure, equipment, capacitation of human resources for health, procurement and distribution of medicines and sundries as well as development, review of health-related legal and policy frameworks. The health sector is governed by a plethora of legal frameworks which include but are not limited to: the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 20) Act, 2013); the Public Health Act [Chapter 15:17]; the National Health Strategy 2021-2025 (NHS) (being crafted); Zimbabwe School Health Policy (ZSHP); the Free User-Fee Policy for pregnant women, children under 5 years and also adults aged 65 years and above; the HIV Prevention Revitalization Roadmap; the Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (ASRH) Strategy; the Zimbabwe Community Health Strategy (2021 – 2024); the Zimbabwe National HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan (ZNASP IV) 2021 – 2025; the National Action Plan for Orphaned and Vulnerable Children (NAP for OVC) and the Mental Health Policy and the National Health Policy.

The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is in the process of developing the National Health Strategy 2021-2025 which outlines the roadmap towards turning around and restoring stability in the country’s health system. Guided by the NDS1, some of the strategic focus of the National Health Strategy include: improved access to essential medicines and commodities; increased access to water, sanitation, and a healthy environment; improved health infrastructure and medical equipment for Health Service Delivery; improved governance of the health service and improved health sector human resources performance and increased domestic funding for health amongst many action plans.

Despite the availability of a myriad of legal and policy frameworks and clear objectives of the vision and mission of the health sector, the health sector has continued to face a plethora of challenges. These challenges include but are not limited to dilapidating and infrastructural gaps, insufficient funding, and brain drain. Poor remuneration has also been at the core of employee demotivation and this has resulted in the recurrence of strikes across the health sector. Since 2019, the country witnessed one of the longest strikes by health personnel over poor working conditions, which nearly crippled the health sector. At the same time, the cost of healthcare continues to increase beyond the means of most citizens, making the SDG target of achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030 a distant ambition. The shortage of medicines and equipment in public hospitals and maternity clinics has become the order of the day. Currently, Zimbabwe is operating with 134 ambulances for a population of approximately 15 million. This means that each ambulance will have to carry approximately 112 411[1].

The health sector has been a victim of brain drain which has been necessitated by poor remunerations and weak strategic human resource management. Approximately, 2000 health professionals resigned in 2021[2] alone, doubling the number of health workers who left the profession in 2020. This militates against the health aspirations as outlined in the NDS1 and vision 2030 which seeks to attain a competitive human capital.

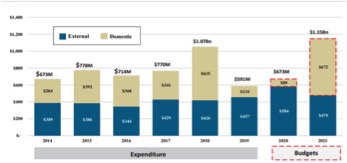

In the 2022 National Budget, Zimbabwe recorded an increase in the national budget allocation for health, in 2021 the health sector was allocated 12,7%, and in 2022 it was given 14.9%. However, despite a positive stride towards fulfilling the Abuja declaration of 15% allocation for health, the government has a culture of not disbursing all the allocated revenue. This can be evidenced by the fact that the health sector only utilised 46% of the allocated revenue, while the agriculture sector had an over-expenditure of 71%. Engagements with an official in the Ministry of Finance who is at the director level during a workshop last year in Kwekwe for Public Expenditure Tracking Survey Training were fruitless as he could not give reasons why the agriculture sector was allowed to overspend while the health sector underspent. Above all, the government needs to change its attitude towards health spending, as an examination of health spending over the last years shows that, the majority of health expenditures are not funded by the government. This might be a deliberate ploy to arm-twist donors and other players to fund the health sector.

Fig 1 below shows the overall funding of the health sector since 2014:

OVERALL FUNDING OF THE HEALTH SECTOR IN ZIMBABWE (2014-2021)

HTTPS://WWW.THEINDEPENDENT.CO.ZW/2021/10/29/NEW-HORIZON-AT-LAST-UN-WILL-WITNESS-WHO-IS- IMPOSING-SANCTIONS-ON-ZIM- 2/#:~:TEXT=ZIMBABWE%20ONLY%20HAS%20134%20FUNCTIONING%20AMBULANCES%20FOR%2015,ZIMBABWEANS%20 TO%20ACCESS%20EMERGENCY%20HEALTH%20CARE%20ON%20TIME.?

MSCLKID=3BAB4FFDB4D811EC9B94A7CF4C42BD53

HTTPS://WWW.THEZIMBABWEMAIL.COM/HEALTH/ZIMBABWEAN-HEALTH-SECTOR-LOSES-2-000-WORKERS-IN-202

3. REGIONAL HEALTH SECTOR PERFORMANCE

Comparatively, the regional key health indicators paint a gloomy picture of Zimbabwe’s health status compared to her neighbours. The clearest indicator of the health crisis in Zimbabwe is the ‘maternal mortality ratio per 100 000 live births’: 458 children are dying compared to 119 in South Africa. All the other countries are better ranked on all indicators except Zambia which is the least ranked on ‘nursing and midwifery personnel density’ and ‘under-five mortality rate’. Of concern is the ‘medical doctors per 10 000 population’ which is around 50% less compared to neighbours Botswana and Namibia and lesser by 75% of neighbours South Africa and Zambia. In the same vein, ‘nursing & midwifery personnel density per 1 000 population’ is less than that in Botswana and Namibia by 50% and lesser than that in South Africa by almost 78%. The continued industrial action by health personnel due to incapacitation worsens the prospects of improved healthcare provision for the poor.

To this end, in Zimbabwe, the health status is compromised as evidenced by a decline in most poverty sensitive health indicators as shown in Table 1. The indicators show the poor health delivery system in Zimbabwe compared to other countries in the region.

The failure of the government to quell industrial action in the health sector for many years and the lack of basic drugs have worsened the plight of the vulnerable hence the poor health indicators.

4. SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC JUSTICE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The concept of social and economic rights has taken center stage in the global arena although it is not a new phenomenon. Social and economic rights fall under second-generation rights. Globally, socio-economic rights can be traced back to the early 20th century when the then agency of the League of Nations, the International Labour Organisation espoused a series of conventions calibrated to improve labour standards across the globe. After the Second World War, a number of conventions and international treaties were ratified these include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR 1948)[1], Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)[2], International Conventions on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR 1966) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)[3] to mention but a few. These treaties and conventions were tailor-made to promote a just and inclusive society that is anchored on social and economic rights. Africa being part of the global community also have the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights which seeks to enforce the realization of social and economic rights for all.

Zimbabwe being a member of the international community and an African state which ratified all the above conventions and treaties recognizes social and economic rights through various legal frameworks. These include the Constitution, social protection policy, and devolution policy to mention but a few. The aforementioned legal frameworks though not exhaustive have a bearing on social and economic rights. Nonetheless, the level of adherence and enforcement has been problematic hence the growth of inequality across the entire sectors of the economy and society. The Health sector has been at the apex, as the cost of health is now beyond the reach of many Zimbabweans. The construction of the VVIP hospital for the political elites and army generals is a testament to the institutionalisation of inequality in the health sector[1]. The hospital is being constructed to the tune of US$ 270 million, the money that could have gone a long way in promoting health access to the vulnerable through Health Assistance Programmes. Therefore, examining the Health Service Amendment Bill under the prism of social and economic justice will be expedient in promoting health equity.

5. PROVISIONS OF HEALTH AMENDMENT SERVICES BILL

The Health Services Commission

The HSAB seeks to align the Health Service Act (HSA) to the constitution by making the Health Service a Commission. The Health Service Commission (HSC) will be at the apex of the health sector.

Functions of the Commission

The functions of the HSC shall be to determine the grades of all employees in the health sector, appoint qualified and skilled personnel, preside over disciplinary hearings, create favourable working conditions for optimum health services, ensure members of the Health Service carry out their duties efficiently and impartially as well as advise the Minister of Health and President on matters related to health. The Commission shall be guided by the principles of good public administration and public finance management as enshrined in sections 194 and 298 of the Constitution respectively.

Composition of the Commission

The commission shall have a minimum of two members and a maximum of five members with the Chairperson at the apex of the commission. The Chairperson of the commission must be the Chairperson of the Civil Service Commission. The deputy chairperson of the Commission and other members shall be appointed by the president upon recommendation by the minister.

The Staff of the Commission

The day to day operations of the commission shall be under the management of the Secretary who will be appointed by the commission. The Secretary of the Commission must be a qualified medical practitioner with administrative skills and a minimum of seven years of experience. The staff of the Commission shall be public offices but not part of the Civil Service.

PROHIBITION OF THE RIGHT TO STRIKE

The HSAB defined the health sector as an “essential service” which is in tandem with the description of “essential service” in the Labour Act [Chapter 28:01]. According to the Labour Act [Chapter 28:01] in conjunction with section 65(3) of the Constitution an “essential service” shall not undertake collective job action whether lawful or unlawful for an uninterrupted period of 72 hours or for more than 72 hours in any given 14-day period. In the event that health personnel intend to do a strike, they must submit in writing 48 hours’ prior to the commencement of the strike. The submission of a written request is not an approval guarantee. The Bill also states that anyone or union which organises a collective job action without the approval of the Commission shall be guilty of an offence liable to a fine not exceeding level 10[1] or imprisonment for a period not exceeding three years or to both such fine and such imprisonment. The Bill further notes that, while on strike, health personnel will be obligated to provide uncompromised services to patients.

6. EMERGING ISSUES

Collective job action parameters

The prescribed collective job action parameters are critical in ensuring the availability of health personnel at their workplaces. However, they undermine employee moral by violating their right to strike. Rather than addressing the real underlining challenges that are creating a fecund ground for job action, the government is making efforts to infringe the rights of health personnel. This is against social and economic rights as prescribed in second generation rights.

HSAB

HSAB does not address the challenges that are militating against inclusive and optimum health service across the country. One of the major weaknesses of the bill is that it does not address inclusive key health provisions such as infant mortality rate which is at 35.02% deaths per 1000 live births[1], at a time when Zimbabweans are still haunted by the nostalgia stillbirth of seven children in one night[2].

Working Conditions, Remunerations and Infrastructural Gaps

The Bill also neglects the working conditions, remunerations and infrastructural gaps in the health sector. The strike by the health personnels which has been recurring since 2019 are motivated by a myriad of complimenting dynamics. One of them being poor health equipment, unavailability of medication and poor remunerations. This led to the mass exodus of 2000 health professionals to other countries in search of greener pastures in 2021 alone[3].

VVIP Hospital

The construction of the VVIP will institutionalise health inequality, the Bill is silent on the construction of the hospital yet it is perpetuating health inequality.

HEALTH SERVICE COMMISSION

The government uses the Bill as a smoke screen of positive strides towards revamping the health sector, while in reality there is no correlation between the Bill and the services that are currently being provided. This is because the functions of the Health Service Commission are just a replica of the Health Service Board and there is nothing new except a change of name. A change of name should neither be confused to favourable working conditions or optimum service delivery as this fits well under the popular old adage “new wine in old bottles”.

Emergency Management

The failure of the Bill to address the country`s emergency management services which is in a dire situation with only 134 functional ambulances[1] for a population of 15 million[2] is a clear testament to the negative correlation between renaming of the Health Service Board to Health Service Commission.

Presidential Appointments

Although the president is the appointing authority, citizens have raised concern over partisan appointments. The public sector has been overshadowed by nepotism and this has undermined the principle of meritocracy. Politically connected people are appointed in strategic and key decision making positions without considering the skills and expertise a scenario which is likely to proliferate in the appointment of the members of the Health Service Commission.

Power Centralisation

The Bill centralises power in the hands of the Chairperson of the Commission who is also the Chairperson of the Public Service Commission. This is against the principles of good public administration as prescribed in section 194 of the Constitution and the Public Entities Corporate Governance Act (Chapter 10:31) which seeks to promote good corporate governance. The principles of good corporate governance are hinged on the segregation of duties for the infusion of transparency and accountability in the operations of an entity.

7. POLICY ALTERNATIVES

- Instead of creating the Health Services Commission, the Ministry of Health must create a conducive working environment, and ensure that there is adequate health equipment and competitive remuneration for all health professionals.

- Although health professionals fall under the category of “essential services” the Ministry of Health must ensure that, the rights of employees to strike is protected and promoted whilst safeguarding the right to life.

- Rather than having a sector specific commission that focuses on health, the government should make use of the Tripartite Negotiating Forum to reinvigorate the social contract to institutionalise and improve social dialogue in the health sector. Anything less to that will culminate in the recurrence of collective job action, go slow or moonlighting.

8. CONCLUSION

The intention of the Bill is problematic because it is undemocratic with respect to the right to strike of health employees, but it is also happening in a context where the accumulation of strikes and poor service delivery has had a negative impact on the lives of patients. Therefore, to preserve life that is lost during strikes, the bill moved in to regulate the conduct of strikes, their nature and their period. Nonetheless, in terms of social and economic justice, the Bill is blind as it does not address the challenges being faced by the health sector. The creation of the Commission does not bring anything positive with respect to the revitalisation of the health sector as it neglects the underlining dynamics that are militating against optimum health service. These include but are not limited to poor remunerations, dilapidating infrastructure, unavailability of medicine and brain drain.

The health sector is not in need of an amendment bill as there are numerous policies and legislative frameworks that are already in place. It only needs commitment by the government to address the legitimate concerns of Health Service professionals without undermining fundamental rights and freedoms