By Charles Dhewa

Due to continuous dependence on imported western knowledge, most African countries have not invested in understanding their own local knowledges. For instance, while these countries continue to lament that they do not have foreign currency and advanced technologies, they are not taking time to reflect and compare what they have in abundance with what they lack. Once they do that they will discover how land, water, sunshine, forests and many other resources are more valuable than foreign currency.

| Imported Knowledge | Indigenous Knowledge |

| Associated with academic education that alienate people from their local communities. The more one gets formally educated, the more s/he loses identity and roots. | Embedded in local context, culture and identity – all these are baked into reliable routines. |

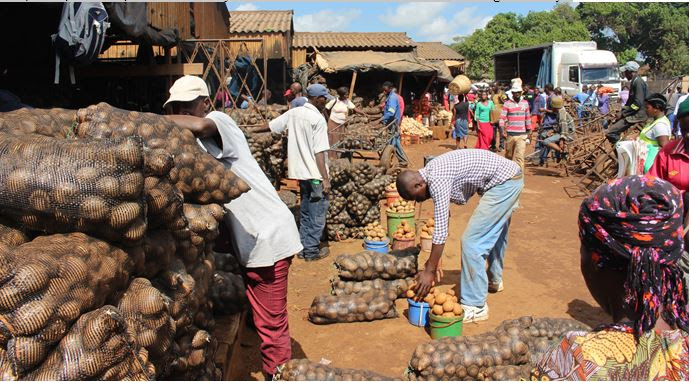

| Formal companies and corporates are a key feature of imported knowledge. | SMEs and informal markets are dominant examples of indigenous entrepreneurs. |

| Cities are part of western knowledge as shown by infrastructure like roads, electricity and airports, among other Western structures in which imported knowledge is embedded. | Imported knowledge in cities draws on resources like culture, labor and natural resources from rural areas where unfortunately little value addition is happening using local knowledge compared to cities where western knowledge is largely used to add value to those resources. |

| Western knowledge is valueless without indigenous knowledge systems used to produce and safe-guard natural resources. You can bring the best technologies into cities but without commodity supplies from rural areas technologies are valueless. | Food system are generated from indigenous economies and brought into western knowledge for value addition. The most important resources are culture, values and traditions. Valuing all these resources brings comparative advantages for African economies. |

| Western knowledge measures agricultural commodities through weighing – scales, kilograms, hectares, litres, etc. Commodities are also valued mostly in monetary terms to a point of saying a cow is worth so many US dollars. |

IKS uses buckets, baskets as well as human senses like taste, smell, touch, hear and sight that are more inclined to IKS. Instead of using monetary terms only, IKS has a lot of value related to social beliefs, economic beliefs and even tradition (if we sell a family bull, how will we replace it?). How do farmers value their commodities in order to come up with a price? |

| Cities talk in terms of unemployment. What do we mean when we say someone is unemployed? How can a city with 96% unemployment continue functioning? How is the city surviving with such high levels of unemployment? In rural areas such levels of unemployment or incapacity may be related to drought or floods. | Rural communities are linked to natural resources and do not talk in terms of employment and unemployment at both individual and community. They speak more in terms of asset ownership in relation to agriculture as well as the needs of individuals and communities. |

| Imported knowledge talks in terms of free trade areas and selling of commodities but knowledge is not considered part of the economic and commodity focus. But there is no clarity on how knowledge traded as part of global trade just like using commercial trade of goods and services. African countries do not have specific avenues for tracking trading of knowledge between countries and commodities. | IKS has strong pathways for knowledge and information exchange combining natural resources, culture, religion, values and other critical factors. |

| African countries have borrowed definitions of the economy and economic growth from imported knowledge. Much of economic growth uses indicators like employment creation, income levels and population growth as well as ICT penetration. But we don’t have knowledge as an indicator or component of economic growth. | IKS thrives on social indicators. Whereas the measurement of Western economies is based on economics, African growth paths are defined by social parameters. Social aspects, which we have not defined at the expense of social indicators include culture, tradition and the whole society. All this has its own growth paths from rural to urban areas. |

| Western platforms are meant to facilitate payment for commodities. The whole notion of platforms was meant for trading commodities without using cash but we have abused it by using it for trading money not commodities. | African countries now have a challenge around the adoption of technology. Mobile money is not an innovation because we have failed to put technology to good use or domesticate it to support our traditional transaction modes. |

| Uses a dollar a day to measure poverty datum line. | IKS uses social indicators like depression among men whose wives go to the diaspora or the small house effect on economic depression. These social indicators are directly linked to the indigenous economy. The roots of an indigenous economy and home-grown economy are social not economic factors. |

| Imported knowledge has become a public good and that is what African universities are investing in instead of venturing into the new and unknown African knowledge. The business cycle for pure knowledge has reached a ceiling and could be seen in the form of sales going down. | A major advantage with Africa is that much of the knowledge is yet to be unearthed and has a lot of value. For Africa it’s more about coping this knowledge than creating new knowledge using new inventions. Wisdom is the basis of the economy. |

| Defines growth as turning land into buildings like sky scrapers for investors or markets. | IKS leaves prime land for producing food systems. Growth should make IKS pure so that the world can come and learn from Africa on how to build an economic power house based on IKS. |

| Promotes monocultures in production, consumption and lifestyles. | Restoring African culture is a good starting point. For instance, what makes a rural African country or district unique? IKS also recognises indigenous institutions like traditional leadership structures. |

| Promotes continuous importation of raw materials and human resources from Africa | IKS would rather invest in valuating our resources and knowledge and then we become champions of exports by selling our products not labor and add value to our commodities. |

| Believes in central policy making and resource management. | IKS is conscious to the fact that devolution should not just be about political power. It is about identity and culture. Resources need to be managed at all levels including policy. Devolution is about opening pathways to receive voices from all angles as well as innovations and initiatives that just need to be supported. |

| Imported scientifically proven knowledge may not change within the next five to 10 years. It represents a comfort zone for academics who are more interested in proven and reliable routines. | IKS recognises that if we remain stuck with proven knowledge of the past, we will not improve. We have to go beyond and venture into the unknown while building on what works well. |

The power of mastering the knowledge value chain

Few initiatives are as important as paying attention to the interface between formal and informal knowledge as well as Western and African knowledge. Processes are critical and so is external knowledge while relationships are important in gaining knowledge. There is no longer any doubt that African countries need a collaborative knowledge base driven by more than 80% of the local people. That is why a clear understanding of the knowledge value chain is critical. It is important to appreciate what you have and try to improve on your weaknesses. While academics find it easy to theorize from a distance, development is about addressing equity and superiority issues between the state and ordinary people, young people and poor people. Formal and informal economies have different knowledge systems and processes. There are also different processes between the public and private sector.