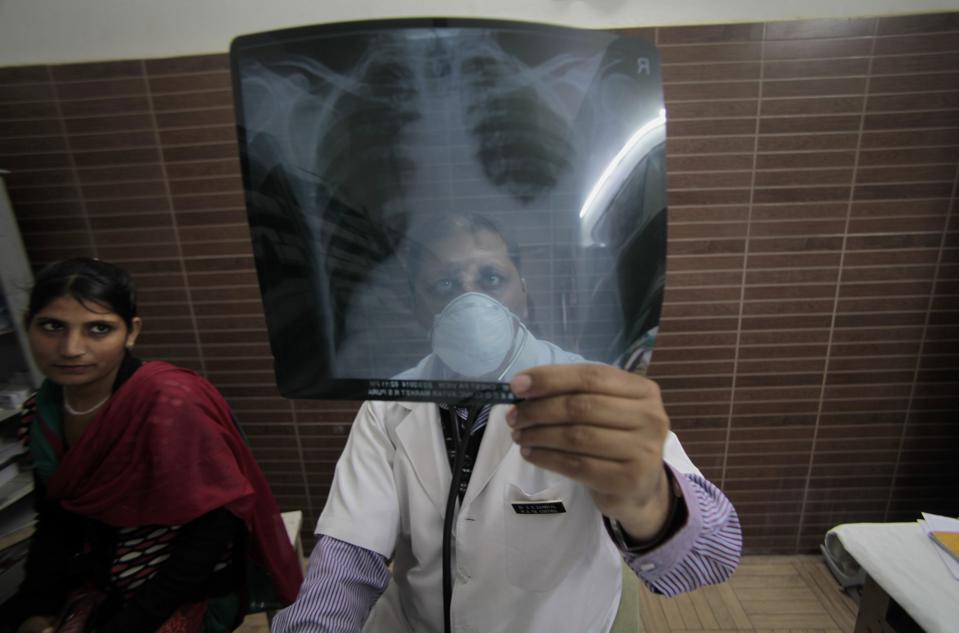

MANILA — Tuberculosis has long suffered from limited tools for testing and treatment, but a new report finds that it also faces policy disparities between what is recommended globally and what is rolled out in countries.

In 2018, governments committed to a set of ambitious targets in the fight against tuberculosis during a United Nations high-level meeting. But the world is far from achieving its targets. Only 14.1 million people were treated for TB in 2018 and 2019 — out of the 40 million target, and only 6.3 million people were started on TB preventive treatment, against the target of 30 million people by 2022, according to the World Health Organization’s latest global TB report published in October.

The Stop TB Partnership and Médecins Sans Frontières have found that a slow uptake of internationally recommended policies contributes to holding back progress against these targets. In their “Step Up for TB 2020” report, they found many countries are still using outdated testing policies.

When it comes to treatment, almost half of the countries surveyed are still using injectable medicines to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis, as opposed to the 2018 global recommendation of an all-oral treatment regimen. In addition, only 24 of the 37 countries indicate having policies in place for shorter TB preventive therapy regimens.

The report also found the majority of countries do not require the approval of a regulatory authority or WHO prequalification for imported or locally manufactured TB medicines, which could put people with TB at risk of being treated with medicines of substandard or unknown quality.

The countries surveyed in the report account for 77% of the global TB burden, according to the report. Countries cite lack of funding and the high price of TB tests and medicines as among the reasons for non- or slow-uptake of globally recommended policies. But there are other factors, such as waiting for pilot results or ongoing operational research on the use of TB LAM tests in countries. Some countries also cite a lack of awareness of WHO-recommended shorter regimens for TB preventive therapy.

Focus on implementation

Cheri Vincent, chief of the Infectious Diseases Division at the U.S. Agency for International Development, said that there is a perception that once a tool is developed, it gets implemented right away. But that is not the case. Getting tools such as TB diagnostics and treatment to reach those who need them at the primary health care level is the “hard road.”

But that’s where the focus should be, and the funding too, she said. However, “there isn’t enough funding. So you have to make those choices of how do you deploy that in a way that, you know, really will reach most people,” she said during an online briefing regarding the report’s launch.

Some of the things USAID has done include providing support in the creation of hub-and-spoke models wherein there is a transportation system in countries that brings TB samples to laboratories with TB diagnostic equipment.

“That’s not ideal. But considering our reality of funding and the systems … we’ve created some of these kind[s] of mechanisms with the ministries of health to be able to get those tools out to people and get people to [have] access to these life-saving diagnostic tools,” she said.

While international organizations have tried to introduce new global TB guidelines in countries, governments are “the most important actors” in bridging the global-national policy gap, said Sharonann Lynch, senior TB policy advisor for MSF’s Access Campaign.

For example, 23 of 37 countries surveyed by the Stop TB Partnership and MSF do not indicate the use of lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay or LF-LAM, a rapid point-of-care test that helps diagnose TB in people with HIV, despite WHO recommendations released in 2015.

“National treatment programs for TB must have the resources they need to make sure testing and treatment can be adopted and implemented immediately. After all, governments have signed on the dotted line to end TB, but they can only do that if they take the proper steps today to get more people tested and put on treatment for TB,” Lynch told Devex.

But donors, too, should ensure there is enough funding available for TB programs, and that “we don’t backslide further by letting COVID-19 distract us while TB remains the world’s deadliest infectious disease,” she added.

About the author

Jenny Lei Ravelo@JennyLeiRavelo

Jenny Lei Ravelo is a Devex Senior Reporter based in Manila. She covers global health, with a particular focus on the World Health Organization, and other development and humanitarian aid trends in Asia Pacific. Prior to Devex, she wrote for ABS-CBN, one of the largest broadcasting networks in the Philippines, and was a copy editor for various international scientific journals. She received her journalism degree from the University of Santo Tomas.