|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Charles Dhewa

The urgency with which farmers seek help, advice, and support increases during the harvesting season compared to the planting season. Production knowledge is now relatively abundant but the same cannot be said about knowledge on markets and their behaviours. During the planting season, the market is the one looking for commodities while farmers are busy in the field. However, the situation changes during the harvesting and marketing season when all farmers begin pushing commodities to the market irrespective of demand levels. This is often good news for consumers, not farmers.

Curse of short value chains

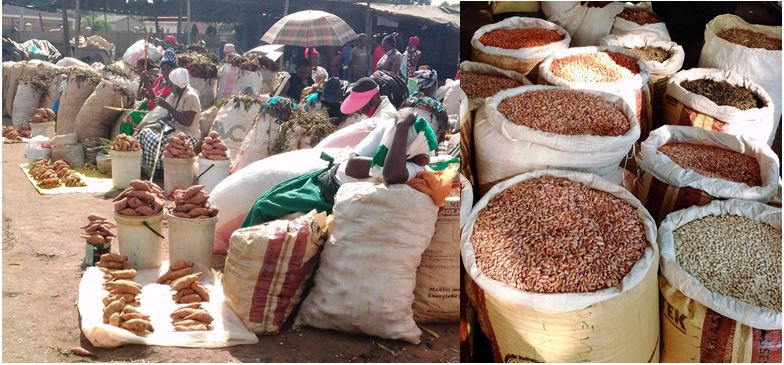

Across Africa, supply chains for most agricultural commodities are very short – farm to fork. Conversely, demand especially from urban consumers does not change by a greater percentage at the household level. For instance, consumers do not suddenly start buying and consuming more pumpkins, fresh groundnuts or any other commodity in response to more production. Since the demand for necessities like tomatoes and vegetables does not change fast, increases in supplies of such commodities exerts pressure on commodities which end up fetching much lower prices than their potential earnings. There is a limit to which consumers can buy extra commodities. Even if a bucket of maize can be sold for USD1, an urban household will not buy a ton of maize grain. Another dynamic is that when a commodity is readily available, consumers will not buy in bulk or hoard because prices remain favourably low. It is when there are shortages that buying in bulk and hoarding becomes rampant, pushing prices up.

The other side of a bumper harvest

Every commodity has a potential price and a premium price which determines the return on investment. If there is a bumper harvest like this season in Southern Africa, prices are suppressed, causing commodities to fetch below normal prices. This trend undervalues the contribution of agriculture to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Where, for instance, under a normal supply situation characterized by normal prices, the agriculture sector can contribute USD1 billion to GDP, under a bumper harvest-induced glut, prices may fall by 50% which means the sector only contributes half a billion dollars.

More importantly, when farmers get below normal prices (50% or less), their potential to purchase inputs also goes down by 50%. That is how the agriculture sector begins to shrink because even if the following year becomes a good rainfall season, this season’s poor prices will constrain farmers’ ability to take advantage of the good rainfall season next year because they will not be able to afford sufficient inputs. Ultimately, this torches a collapse of entire agriculture-driven economies as the impact stretches to downstream and upstream industries.

Ensuring quality control within supply chains and farming systems

The absence of quality control has remained another major challenge in African food systems for decades. When most commodities are coming from the field during the harvest period, quality differences are very minimal as commodities from individual farmers will be very similar in quality. However, if farmers take the commodity for storing in their individual stores, quality levels become very different such that quality gaps become so huge. This is because farmers have the different infrastructure, storage, and handling facilities as well as pre and post-harvest knowledge. Many do not have the right stores and some commodities are exposed to rodents as well as different impurities. To that end, aggregating commodities when they have been exposed to different storage facilities and handling techniques make it impossible to get commodities of the same quality.

That is why aggregation has to be done timely – just as commodities are leaving the field before quality variances increase. This is where the notion of a Warehouse Receipt System (WRS) becomes relevant. The WRS should be built from the bottom starting with the aggregation of commodities. It does not start with issuing receipts. Neither should it just be about collateral if farmers are to be convinced about its benefits. A thorough baseline study can ensure the WRS is tailored to the real needs of farmers.

Importance of matching supply with demand

The importance of coordinating and regulate commodity supplies to the market as part of averting huge losses cannot be over-emphasized. Supply patterns are often pushed by the absence of alternative markets like preservation, processing, and value addition. In most African countries there is definite need for infrastructure and systems that spread the supply of commodities all-year-round especially given that the bulk of food commodities are seasonal. Ensuring commodity supply all year round translates to ensuring availability of nutrition baskets all year round and extending food to low producing areas.

For home-grown commodities, communities and farmers have more control over prices or return on investment unlike internationally traded commodities like tobacco and minerals whose prices are determined by international forces of supply and demand. When each country is able to put in place systems for managing its food system throughout the year, that mechanism becomes a strong foundation for comparative advantage trading.

As African countries export food, importing countries will be using African commodities to build their food systems and food baskets including processing industries. Western countries have invested in infrastructure and facilities for warehousing and preserving commodities for a long time. Questions that exporting African countries should ask themselves include: how are importing countries keeping bananas, peas, blueberries, and other commodities throughout the year? Most African countries are only interesting in earning foreign currency and not drawing lessons on how to preserve commodities throughout the year from developed economies that are importing commodities from Africa.