By Charles Dhewa

There is no shortage of abandoned small to medium-scale food processing plants in many African countries. After getting into a community and seeing abundant tomatoes, mangoes, pineapples, and many other types of fruits, some development agencies and government departments have been compelled to mobilize resources for setting up a processing plant. However, a few years down the road, the processing plant becomes a white elephant in the community. Very few food processing and value-addition enterprises have survived beyond five years. Why?

Differences between a commercial approach and a developmental approach

It might seem those processing companies that do not invest in food processing and value addition at the community level have no eyes for business opportunities. However, the reality is that the private sector is very good at conducting informative investment analysis than government departments and development organizations. Good intentions are not good enough in business. That is why most well-intentioned interventions by development organizations collapse as soon as donor funding ceases. Where adequate baseline information on the viability of most community food processing enterprises is available, corporates and financial institutions would invest with no need for persuasion from the government or development organizations.

Development organizations that promote food processing and value addition of fruits, tomatoes, small grains, and other commodities often do so from a developmental or humanitarian perspective. The assumption is that investing in food processing and value addition will lift people out of poverty and create local employment. A related expectation is that setting up a food processing plant in production zones will reduce losses of raw commodities. While all this makes a lot of sense to well-intentioned organizations and laypeople, a commercial perspective sees things differently and it is often the commercial perspective that tends to be correct in the short run. Huge volumes of raw fruits and tomatoes have been finding their way to cities from rural areas because a business case for local-level food processing and value addition has been very difficult to sustain.

Absence of deep investment analysis and business plan

What is often missing in most food processing projects whose benefits seem obvious, is a deep and broad investment analysis. In most cases, authentic information about the level of competition, consumption patterns, local consumer buying power, and socio-cultural aspects is missing with too much focus on putting up infrastructure like warehouses, sheds and processing equipment.

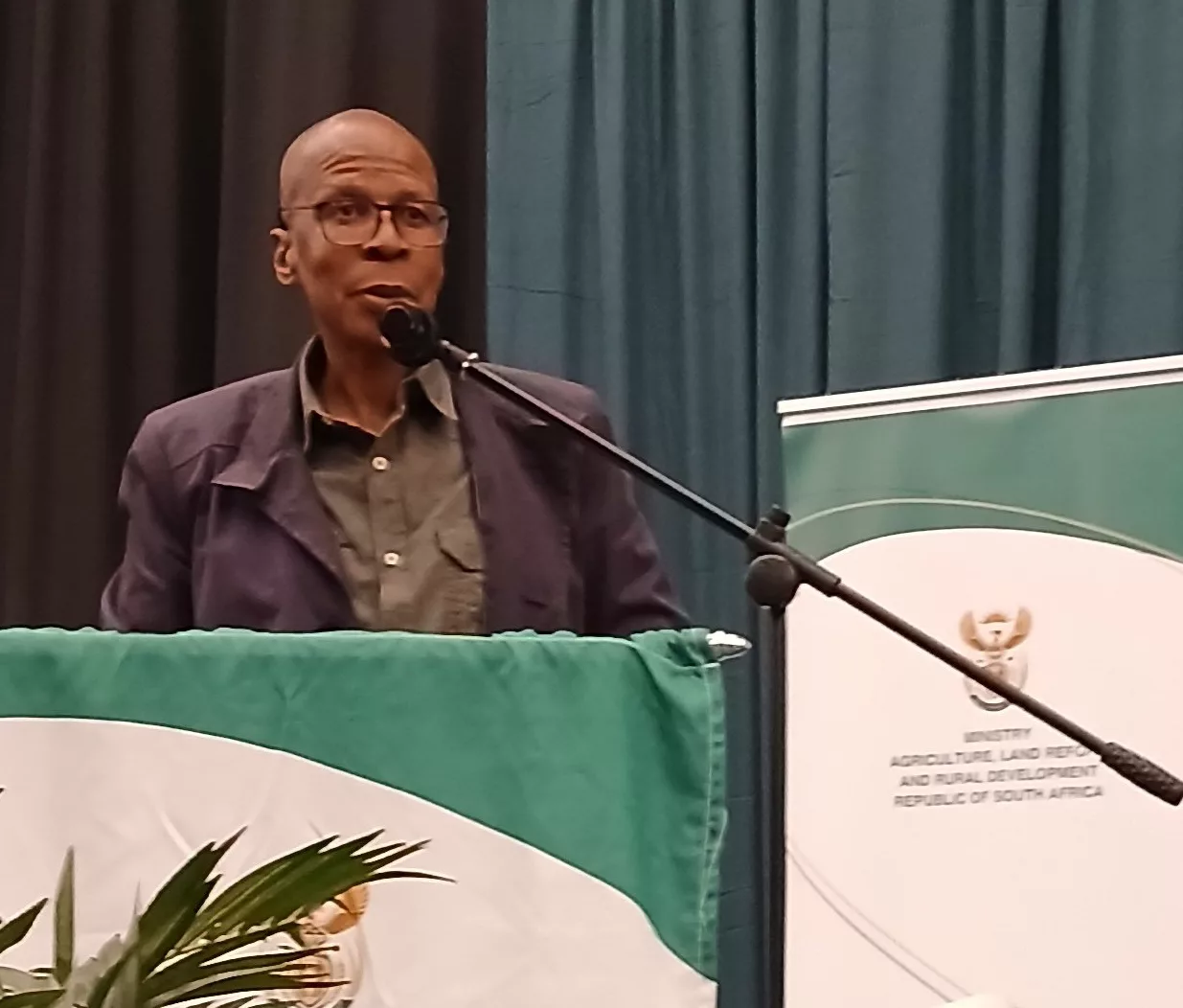

More than two years ago, a tomato processing plant was set up at Tabudirira Vocational Training Centre in the Mutoko district of Zimbabwe. The district is famous for tomato production among other horticulture commodities. Funded by the African Development Bank to the tune of USD1 million, the plant is a good example of why an investment analysis is very important. The day it was officially launched by President ED Mnangagwa was one of the few days it was seen processing tomato paste and packaging some vegetables. Ever since operation has been on and off due to several reasons that could have been addressed at the investment analysis stage.

One of the major lessons from the Mutoko case is that setting up a food processing plant far from other business activities is a recipe for failure because it becomes isolated from other business hubs. Another key lesson is that a single production zone may not adequately supply raw materials for a local processing plant to make it viable. Given that fresh tomatoes have other multiple uses like household consumption, the processing plant competes with the open market where the majority of household consumers buy their tomatoes. Instead of establishing a food processing plant in one production zone, setting it up at central locations where commodities can be pulled from diverse production zones makes business sense as this ensures a consistent supply of raw commodities.

Achieving inclusive economic transformation through asking the right questions

The good thing about an investment analysis is that it seeks answers to critical business and viability questions. Some businesses often open and seem to do well for a while but soon close unannounced because investors will have ignored key business fundamentals. Where it seems a food processing plant would be a better solution, asking deep questions will reveal invisible ecosystems that can make or break a new enterprise. Instead of focusing on how to make food processing and markets work for the poor, policymakers, businesses and NGOs should turn around the question to focus on how the majority of smallholder farmers, traders, SMEs, rural people, and consumers are making markets work for themselves.

If there is no appetite for processed food in the local production zone, it will be difficult to push the commodity elsewhere. Rural communities are not just victims waiting for donors or government assistance to set up a food processing plant. By paying too much attention to the potential of modern, formal, and global markets, policymakers may not recognize the reality of a thriving local informal and hybrid economy. This has a bearing on whether a new intervention like food processing can survive or not.

The power of income diversification

Most African economies are characterized by a diversity of smallholder livelihoods combining formal and informal, farm and off-farm, and urban and rural activities which bring together SMEs, farmers, traders, and other actors to collectively shape the rules of the hybrid economy. Food processing enterprises have to compete in contexts where flexible informal channels link poor smallholder farmers with poor urban consumers, connected by raw food commodities like tomatoes that are more affordable than processed tomato sauce.

Verbal agreements account for the circulation of considerable volumes of agricultural commodities as a way of overcoming obstacles typical of commodity markets in developing countries – poor market institutions and imperfect information. What is also becoming clear is that Informal does not mean uncoordinated. Far from being at arms-length, informal and traditional trade is often marked with high degrees of coordination, based on trust-based networks through which food moves from rural to urban and vice-versa.

Confirming the fact that economic transformation is not a magic bullet, the livelihoods of economic actors in African hybrid economies have become complex mixtures involving multiple informal arrangements. A defining feature is increasing interweaving of rural and urban economies with farming activities being combined with off-farm work through increasing urban-rural linkages. Traditionally, urban incomes have been so low that many people have had to supplement their wages with food from rural areas, sent by relatives on bus careers. The situation has changed markedly.

Extensive kinship links allow rural farmers, for example, to rely on working periodically at urban relatives’ shops and workshops or as housemaids in cities or growth points. Improvement of roads and a boom in transportation between rural and urban areas are facilitating circulation from farm to city, and many villages have become towns. As rural marketplaces are also growing stronger and more connected to urban markets, rural-urban economic relationships are becoming more fluid, blurring frontiers between these spaces. All this is influencing the demand for processed food.