|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

COP29 is attempting to replace the supposedly “met” political target of $100 billion with a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance amid tactics of filibustering. Is Africa ready for calls of radical approaches and decisions?

By Martha Bekele, Co-founder and Head of Financing at DevTransform; And Wellington Madumira, Coordinator for Climate Action Network Zimbabwe

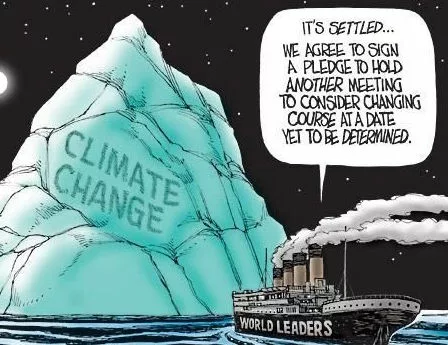

On the very first day of COP29, the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) was unequivocally strong in opposing the introduction of a new text of the negotiation framework for the New Collective Quantified Goa (NCQG). This resistance delayed the decision on the agenda until late into the night. However, even after the agenda was finalised, significant divisions between Global North and Global South parties remain, making it highly unlikely that COP29 will deliver a climate finance commitment.

If COP29, dubbed the ‘climate finance COP’ fails to deliver on finance it will decisively seal its fate as a failure amid calls for a comprehensive overhaul of the COP process and the global system, which continue to deal Africa the worst hand in global relations.

So, what are the issues at stake for Africa? What options does the continent have for financing climate action and ensuring that polluters pay? Most importantly, how can Africa assert its agency to address persistent inequities in global climate finance in the years to come?

Stakes at COP29

By the end of the first week of technical negotiations, no agreement had been reached on the framework for negotiating the new collective quantified goal – a commitment on climate finance to support Global South countries in undertaking climate action. This goal is intended to replace the supposedly “met” and even surpassed $100billion per year commitment by developed countries. With accounting tricks and games of numbers, this claim has been widely discredited. Investigations have revealed that absurd investments by developed countries in developing countries, such as opening chocolate and gelato stores, were reported as climate finance, and some were wrongly tagged as climate finance in the tune of billions dollars.

The Baku negotiations therefore focus not only on the quantum but also the quality and structure of the new climate finance goal. The first week in Baku was concluded without agreement as developing countries put down an ask of US$1.3 trillion per year by 2030 although this ask should have been higher. Developed countries, by the close of the first week of COP29 technical negotiations, made no counteroffer. Instead, they sought to frame climate finance as mainly a private sector affair, through so-called ‘multilayered’ investments goal, proposed sharing the financial burden with other developing countries, and raised other contentious issues such as carbon markets that are likely to be unacceptable to the Global South.

So, after 29 years of negotiations, there is currently absolutely no discussion of reparations. Instead, the focus is on who will pay for climate finance, aside from the historical polluters, how to involve the private sector, and the use of concessional loans—without even a common definition of what constitutes climate finance.

What options does Africa, a continent with the the lowest contribution to global warming have in this context?

Reckoning with the past

Africa’s engagement in climate talks – whether on financing, emissions reductions, entitlement to any loss and damage from the climate crisis or its ability to adapt to climate change – must be understood through the lens of historical articulation into the global capitalist economic system: from slavery and colonialism to the ongoing neocolonial exploitation. The Global North’s dominance and the plundering of Africa’s people and resources demand moral and financial recognition of Africa’s rightful place in global relations. This stretches back to 1619 when the first Portuguese slave ships arrived and continued through the “Scramble for Africa” in the 1880s. While colonialism supposedly ended in the 1960s, Africa remains under neo-colonial control as perfectly reflected in its global economic and political relations. The exploitation of Africa’s resources today – the demand for “critical minerals” in the energy transition – mirrors this history.

We should also recall that the call for financing loss and damage from the climate crisis began in 1991, with Vanuatu’s submission to establish an international fund to address climate impacts. The current understanding of loss and damage is, in fact, a compromise between ‘liability and compensation’ and ‘risk management and insurance.’ The latter view has ultimately prevailed. Nowhere in the Paris Agreement is there mention of liability, reparations, or compensation -these are the compromises the Global South has been forced to make.

Claiming power: call for radical approaches and action

To assert its agency and claim the power to shape its economic, climate, and political future, Africa can follow a combination of strategic, diplomatic, and structural approaches.

The road to economic independence

Support tax initiatives

Africa is losing $88.6 billion per year equivalent to 3.7% every year to illicit financial flows, equivalent to 3.7% of its GDP, a staggering sum far exceeding what is coming in as ‘aid’ ($48 billion) and foreign direct investment ($54 billion) that the continent receives annually. This outflow, which excludes the effects of the brain drain, is a glaring manifestation of the continent not realising its power. While Africa struggles with resource depletion and financial hardship, ‘clean countries’ serve as safe havens for illicit wealth. London, for instance, has become the dirty money capital of the world.

Meanwhile, in contrast to this capital flight, international taxation rules are evolving. On August 16, 2024, the UN Tax Convention’s Terms of Reference (ToR) were adopted, marking a victory for Global South solidarity against the Global North. This progressive tax framework, born from decades of advocacy, promises to establish fairer global tax regulations and deliver the essential funding required for development and addressing climate challenges. The wealth exists; it’s just being hoarded in the hands of the super-rich and polluters. Progressive tax models – such as carbon-based wealth taxes and windfall taxes – can generate the resources needed to address both historical injustices and future climate challenges. Africa must push for these resources to be redirected into the continent’s hands, with historical polluters bearing the brunt of responsibility. Support for the UN Tax Convention is key in this struggle for financial justice.

Beyond reform talks

Africa’s path to true economic autonomy starts with breaking the cycle of dollar-dominated global lending practices. The current system forces Africa to borrow in foreign currencies, export resources and goods that it does not consume to repay debt, and perpetuate an endless, destructive cycle.

While reforming the global financial architecture is essential, the conversation around reform often merely applies a band-aid to the system. The roles of the World Bank and IMF should be limited to strengthening state-owned national development banks. These institutions are better equipped to address the continent’s long-term climate and development needs. By supporting the growth and credit ratings of these banks, it is possible to build strong, locally oriented financial institutions capable of lending in local currencies.

To achieve economic sovereignty, climate activism must also link itself to efforts to debt relief campaigns, advocating for loans to be converted into grant equivalency through debt cancellation. Any restructuring of debt must be overseen by an independent institution – not the IMF – so that Africa’s financial future is no longer dictated by international creditors.

Building Pan-African Unity and Cooperation

Africa needs to be a unified bloc – akin to the European Union – as a single party to the Paris Agreement, representing the entire continent’s interests. Africa has a negotiating architecture with the Committee of African Heads of State on Climate Change (CAHOSCC) at the top, directing the African Ministerial Committee on Environment (AMCEN) on the political imperatives of the continent, and the AMCEN in turn translating these into directions for the technical negotiating teams under the umbrella of the African Group of Negotiators (AGN).

Currently, while the AGN plays a key technical role, Africa is not a party to the UNFCCC, limiting its political ability to assert collective agency. The fragmentation of efforts is further evident in the presence of individual country pavilions at COP, which are not only expensive but also dilute Africa’s presence. Why are we spending resources on separate pavilions when we could pool our efforts to represent a unified Africa at the African Pavilion?

A recent conversation with an EU delegate revealed that while some EU countries run individual pavilions, their political engagement remains unified under the EU. In fact, some EU members treat COP as a trade fair, where governments, NGOs, and the private sector discuss investments, while political negotiations remain under the EU’s unified representation. This model offers a valuable lesson for Africa, demonstrating the power of a cohesive and coordinated approach.

Wait for fate or retaliate?

Besides the direct impacts of a changing climate, Africa is also subject to the debilitating impacts of the unilateral climate response measures of the global North. Measures such as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and deforestation legislation pose potentially significant negative impacts on Africa’s trade. The EU is using CBAM not only as a non-tariff barrier but also to retain its domestic investors within its jurisdiction. Moreover, the potential threat posed by the Trump campaign’s credible signal to withdraw from the Paris Agreement can weaken the multilateral climate governance regime. The key question is: will Africa simply resign itself, waiting for fate to dictate its future, or will it respond with decisive retaliatory measures?

In the case of CBAM, Africa could, while exploring alternative markets beyond the EU, such as the BRICS and intra-regional trade, impose retaliatory trade measures. However, this requires the African countries to constitute themselves into a single trade bloc, capable of regulating trade relations with the rest of the world. On the issue of Trump’s stance, some activists are even calling for the closure of American embassies across the continent, arguing that true independence lies in boldness.

Stop the Pillage

A recent report revealed that China has effectively ‘broken the market for critical minerals’, particularly cobalt and lithium. Upon closer examination, the trail leads to the Democratic Republic of Congo. Meanwhile, reflecting on the recent events in Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey, one is left questioning what it will take for Africa’s political elites to put an end to the continent’s ongoing plundering.

Are we, once again, signing deals left and right, mortgaging our resources to support the world’s transition to a greener future, selling our carbon credits to bolster others’ competitive edge for a green world – while we remain entrenched in poverty and desperation, begging for grants at climate talks? It’s time to make proactive decisions, stop the haemorrhaging, and sever the lifeline of extractivism. Africa must hold out for a deal that genuinely benefits the continent before continuing this one-sided exploitation.