By Martin Hart-Landsberg

There are reasons to believe that this strategy is seriously flawed, with working people, including in China, destined to pay a high price for its shortcomings

China’s growth rate remains impressive, even if on the decline. The country’s continuing economic gains owe much to the Chinese state’s (1) still considerable ability to direct the activity of critical economic enterprises and sectors such as finance, (2) commitment to policies of economic expansion, and (3) flexibility in economic strategy. It appears that China’s leaders view their recently adopted One Belt, One Road Initiative as key to the country’s future economic vitality. However, there are reasons to believe that this strategy is seriously flawed, with working people, including in China, destined to pay a high price for its shortcomings.

Chinese growth trends downward

China grew rapidly over the decades of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s with production and investment increasingly powered by the country’s growing integration into regional cross-border production networks. By 2002 China had become the world’s biggest recipient of foreign direct investment and by 2009 it had overtaken Germany to become the world’s biggest exporter. Not surprisingly, the Great Recession and the decline in world trade that followed represented a major challenge (https://bit.ly/

The government’s response was to counter the effects of declining external demand with a major investment program (https://nyti.ms/

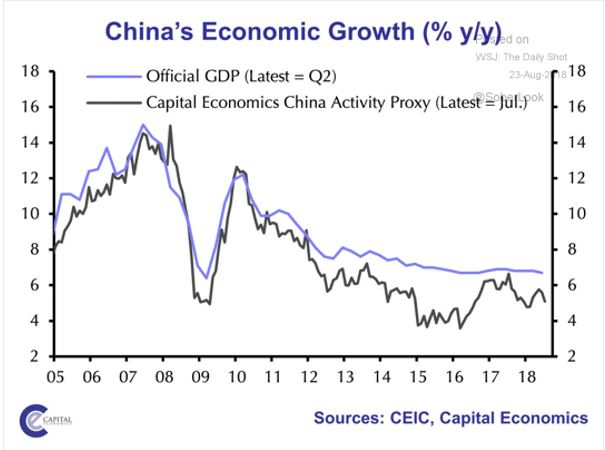

But, despite the government’s efforts, growth steadily declined, from 10.6% in 2010 to 6.7% in 2016, before registering an increase of 6.9% in 2017. See the chart below. (https://bit.ly/

Beginning in 2012, the Chinese government began promoting the idea of a “new normal”—centred around a target rate of growth of 6.5%. The government claimed that the benefits of this new normal growth rate would include greater stability and a more domestically-oriented growth process that would benefit Chinese workers.

However, in contrast to its rhetoric, the state continued to pursue a high grow rate by promoting a massive state-supported construction boom tied to a policy of expanded urbanisation. New roads, railways, airports, shopping centres, and apartment complexes were built.

As might be expected, such a big construction push has left the country with excess facilities and infrastructure, highlighted by a growing number of ghost towns. As the South China Morning Post describes: (https://bit.ly/2St6rzP)

Six skyscrapers overlooking a huge, man-made lake once seemed like a dazzling illustration of a city’s ambition, the transformation of desert on the edge of Ordos in Inner Mongolia into a gleaming residential and commercial complex to help secure its future prosperity.

At noon on a cold winter’s day the reality seemed rather different.

Only a handful of people could be seen entering or exiting the buildings, with hardly a trace of activity in the 42-storey skyscrapers.

The complex opened five years ago, but just three of its buildings have been sold to the city government and another is occupied by its developer, a bank and an energy company. The remaining two are empty–gates blocked and dust piled on the ground.

Ordos, however, was just one project in China’s rush to urbanise. The nation used more cement in the three years from 2011 to 2013 than the United States used in the entire 20th century. . . .

Other mostly empty ghost towns can be found across China, including the Yujiapu financial district in Tianjin, the Chenggong district in Kunming in Yunnan and Yingkou in Liaoning province.

This building boom was financed by a rapid increase in debt, creating repayment concerns. Corporate debt in particular soared, as shown below, but local government and household debt also grew substantially.

The boom also caused several industries to dramatically increase their scale of production, creating serious overcapacity problems. As the researcher Xin Zhang points out:

Over the past decade, scholars and government officials have held a stable consensus that “nine traditional industries” in China are most severely exposed to the excess capacity problem: steel, cement, plate glass, electrolytic aluminium, coal, ship-building, solar energy, wind energy and petrochemical. All of these nine sectors are related to energy, infrastructural construction and real estate development, reflecting the nature of a heavily investment-driven economy for China.

Not surprisingly, this situation has also led to a significant decline in economy-wide rates of return. According to Xin Zhang:

despite strong overall growth performance, the capital return rate of the Chinese economy has started to be on a sharp decline recently. Although the results vary by different estimation methods, research in and outside China points out a recent downward trend. For example, two economists show that all through the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, the capital return rate of the Chinese economy had been relatively stable at about 0.22, much higher than the U.S. counterpart. However, since the mid-1990s, the capital return rate experienced more ups and downs, until the dramatic drop to about 0.14 in 2013. Since then, the return to capital within Chinese economy has decreased even further, creating the phenomenon of a “capital glut”.

In other words, it was becoming increasingly unlikely (https://bit.ly/

Since 2015, the specter of capital flight has been haunting the Chinese economy. In that year, faced with the threat of a currency devaluation and an aggressive anti-corruption campaign, investors and savers began moving their wealth out of China. The outflow was so large that the central bank was forced to spend more than $1 trillion of its foreign exchange reserves to defend the exchange rate.

The Chinese government was eventually able to dam up the flow of capital out of its borders by imposing strict capital controls, and China’s balance of payments, exchange rate and foreign currency reserves have all stabilised. But even the largest dam cannot stop the rain; it can only keep water from flowing further downstream. There are now several signs that the conditions that originally led to the first massive wave of capital flight have returned. The strength of China’s capital controls might soon be put to the test.

Chinese leaders were not blind to the mounting economic difficulties. Limits to domestic construction were apparent, as was the danger that unused buildings and factories coupled with excess capacity in key industries could easily trigger widespread defaults on the part of borrowers and threaten the stability of the financial sector. Growing labor activism on the part of workers struggling with low salaries and dangerous working conditions added to their concern.

However, despite earlier voiced support for the notion of a “new normal” growth tied to slower but more worker-friendly and domestically-oriented economic activity, the party leadership appears to have chosen a new strategy, one that seeks to maintain the existing growth process by expanding it beyond China’s national borders: its One Belt and One Road Initiative.