By Max Bearak and Joanna Slater

NAIROBI — The novel coronavirus is racing toward a collision with two longer-running pandemics, as waves of HIV and tuberculosis infections have left tens of millions of people in the developing world particularly vulnerable to the new threat.

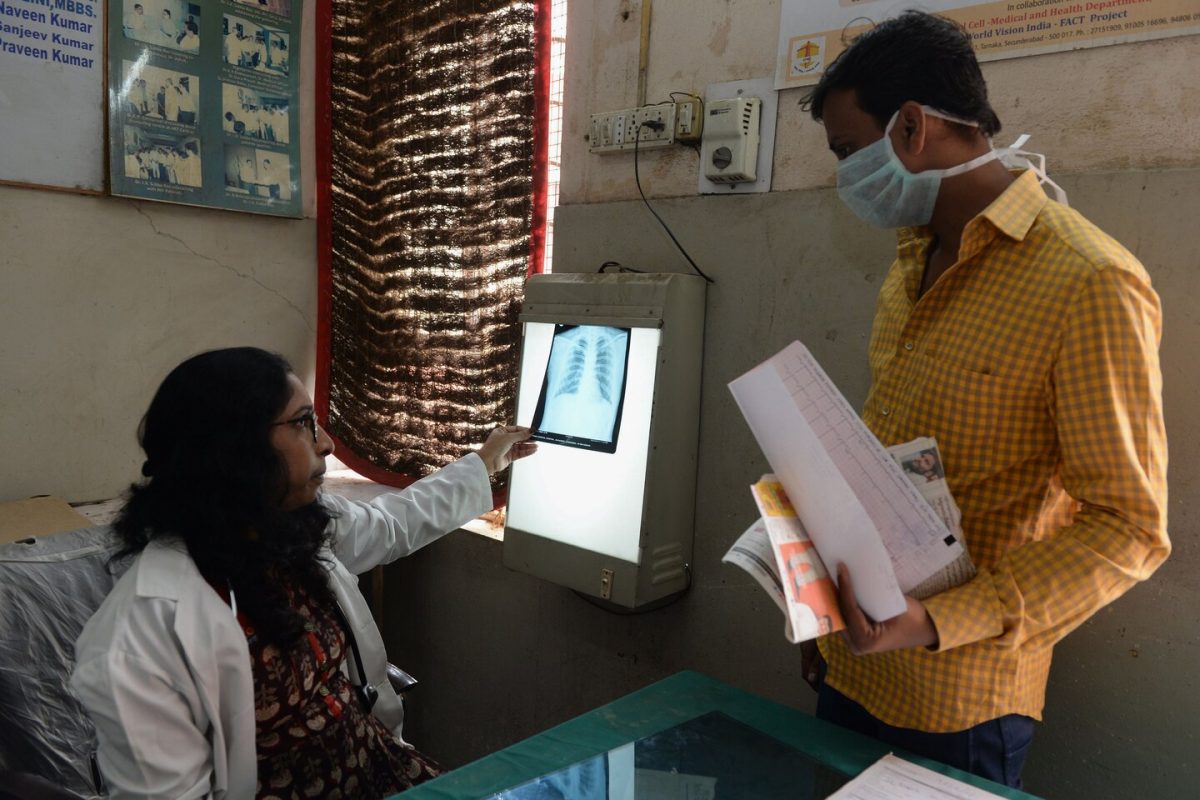

The regions hit hardest by HIV and tuberculosis are in Africa and South Asia, where the coronavirus is spreading rapidly. The countries most at risk include South Africa, home to the world’s largest number of HIV-positive people, and India, which has the highest number of tuberculosis cases in the world.

HIV and tuberculosis are present almost everywhere around the globe. Tuberculosis has spread in recurring pandemics for hundreds of years, killing at its peak in the 19th century an estimated quarter of Europe’s population. More than 1 million still die of tuberculosis each year. HIV reached pandemic stage in the 1980s and has killed at least 32 million people. Around 40 million people currently live with HIV.

Experts expect covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, to affect carriers of HIV and tuberculosis disproportionately, and border closures and crowded hospitals may make it harder for them to get treatment even if they escape the virus.

South Africa is a simultaneous epicenter of all three pandemics. The country is home to 20 percent of the world’s tuberculosis cases as well as 20 percent of the world’s HIV-positive population — nearly 8 million people — and has the largest confirmed covid-19 count in Africa, at more than 2,000.

“We are preparing for the worst,” said Salim Abdool Karim, a South African infectious-disease specialist who is on the country’s presidential coronavirus task force.

That vulnerability has spurred the government there to take quicker and more drastic action in attempting to slow the spread of the coronavirus. It has also meant that HIV and tuberculosis experts are well represented on the country’s coronavirus task force.

“When you look at the data from Wuhan, [China,] the worst affected were above 70 years old,” Karim said. “We are preparing for a scenario where it looks similar in HIV and tuberculosis patients — a death rate in the region of 10 percent.”

Covid-19 hasn’t been around long enough for conclusive studies to be completed on its relationship with HIV and tuberculosis, but the risks are readily apparent. Tuberculosis is primarily a respiratory disease, like covid-19, which means that those who suffer from it often have severely diminished lung health. And HIV causes a progressive failure of the immune system, leaving carriers more susceptible to death from other infections.

Some experts fear that deaths from tuberculosis in India could double in the next year or two. Already, more than 1,000 Indians die of tuberculosis every day.

For tuberculosis survivors like Deepti Chavan, 37, covid-19 is a terrifying prospect. She was cured of a multi-drug-resistant strain of tuberculosis in 2005, but lost one of her lungs. Her remaining lung is ravaged by a type of fungus.

She has spent most of the last month isolated in the one-bedroom apartment she shares with her parents in Mumbai. She stays in the bedroom, and her parents eat and sleep in the living room.

If the coronavirus is “taking the lives of normal healthy people with two lungs, I don’t think we have any chance of surviving,” she said. Her only option is to isolate herself until the pandemic is over. “I won’t be able to come out even after the government says it’s safe to venture out,” she said.

Experts are basing some of their assumptions about how covid-19 will interact with HIV and tuberculosis on studies that link them with influenza, even if the comparison is inexact. The coronavirus has proven to be deadlier than the common flu, especially among the elderly, and the working assumption of most experts is that it will also have a greater effect on immunocompromised populations.

“Modeling studies suggest more flu and more severe flu in tuberculosis patients than in someone who is healthy. And in some cases, flu can trigger active tuberculosis in latent tuberculosis cases. The flu can act as a stressor, and a trigger,” said Nesri Padayatchi, who has studied tuberculosis in South Africa for 25 years. More than 2 billion people around the world carry a latent form of tuberculosis.

But even if experts’ worst fears about the interaction of the diseases aren’t true, ruptures in pharmaceutical supply chains due to border closures as well as the diversion of local medical resources away from HIV and tuberculosis treatment could still jeopardize millions of lives.

“The collateral damage of all this is going to be immense,” said Madhukar Pai, an epidemiologist who heads the McGill International TB Center in Canada. If covid-19 spreads widely in lower-income countries, all the gains made against tuberculosis in recent years will be “unraveled,” he said.

Initial reports from China and South Korea indicate that the coronavirus has disrupted care for tuberculosis patients in those countries, Pai said. Medical personnel are being diverted to tend to people infected with the coronavirus, and wards for patients suffering from drug-resistant tuberculosis have been repurposed to serve as coronavirus isolation wards.

Countries with poorer health systems in eastern and southern Africa that, unlike India, don’t have pharmaceutical industries are also facing the prospect of running out of drugs.

Kenya’s borders have been closed for weeks, and the supply of antiretroviral drugs is uncertain. Like many African countries, Kenya limits users of antiretroviral drugs to one-month prescriptions because of limited supply. Now, the crowds that gather at clinics every month to collect the drugs are ideal locations for the coronavirus to spread.

Experts are particularly worried about countries like Kenya, but unsurprisingly, attention has been concentrated on South Africa, which continues to bear the brunt of both the HIV and TB pandemics.

The country is in the midst of a weeks-long lockdown, and 10,000 health workers are going door to door across the country to test people, as well as to locate where people with HIV and tuberculosis are living.

That challenge is compounded by an estimated 2 million South Africans who have HIV but are undiagnosed, and a large number of other people who are thought to be taking their antiretroviral drugs inconsistently, which can leave the immune system more vulnerable.

“We’re rapidly establishing a central data repository that will house all strategic information, such as people’s HIV status, for example, as well as other medical records,” said Ian Sanne, another member of South Africa’s coronavirus task force, who is designing interventions in consultation with President Cyril Ramaphosa. “That data can be combined with related movement data. Since this is deemed a national security issue, we are able to use people’s cellphone data to a certain extent to monitor movements, too.”

The data will be used to identify locations where hot spots are likely to occur — or are occurring already — and where to build field treatment centers, said Sanne.

India is also in the middle of a three-week lockdown, including a ban on nearly all public transportation. More than 1.3 billion people have been asked to stay in their homes except to buy food or medicine. That has spurred an exodus of workers who are leaving cities on foot after their jobs disappeared and they faced a struggle for survival.

While India and South Africa have relatively robust medical systems compared with those of other developing countries, the lockdowns have left millions with HIV and tuberculosis uncertain of how they will access the treatments necessary to manage their chronic conditions. The lockdowns in effect thrust a disproportionate impact of the coronavirus onto poorer and sicker people.

“Ensuring continuity of treatment for the already sick is at the top of our agenda,” said Michel Yao, the World Health Organization’s emergency operations manager in Africa. He stressed that in the developing world, it isn’t just HIV and tuberculosis that governments should worry about, but malaria, which affects more than 200 million people annually, mostly in Africa, and malnutrition, which affects nearly 1 billion.

Public health activists are urging swift action by governments across the developing world to ensure that HIV and tuberculosis patients don’t lose access to treatment.

Kenya, despite having recorded only about 190 confirmed covid-19 cases, is likely to impose a lockdown in the coming days, and the country’s Health Ministry has already begun strongly advising people not to leave their homes. But the guidance on one-month antiretroviral prescriptions remains in place.

“If a lockdown comes to Kenya, a complete one, we simply don’t know if there are enough [antiretroviral drugs] in the country to treat our HIV-positive people, or what strategy the government has to get them,” said Nelson Otuoma, who directs a nonprofit that advocates for people with HIV in Kenya.

“HIV-positive people here are more scared they won’t get treatment, or won’t even be let into the hospital, than of getting this new disease.

SOURCE: The Washington Post