|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Genome editing, with its immense potential to revolutionize various aspects of human life, holds an important place in the realm of scientific discoveries.

The GE programme is being run in eight African Countries and these are Ghana, Mozambique, Malawi, Kenya, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe. Some of these countries have regulations on Genome Edited (GE) products, and in others, the GE tools are being utilized. For example, Kenya uses the tools for the development of striga-resistant sorghum.

The Government of Zimbabwe has embraced GE technology, and through the Scientific and Industrial Research and Development Centre (SIRDC) together with the regulator the National Biotechnology Authority (NBA) has led in the crafting of a National Genome Editing Communication and Advocacy Strategy, (GECAS). This strategy shows commitment to harnessing the power of cutting-edge technology for the benefit of the country and its people through transparent, honest, and timely communication.

Mrs Florence Nazare, the AUDA-NEPAD’s Head of Centres of Excellence Knowledge Management and Programme Evaluation Directorate said the potential applications of genome editing in agriculture can help in the development of crops that are more resistant to diseases, pests, and environmental stresses.

“This, in turn, will enhance food security and contribute to the well-being of the nation, as livelihoods are improved. Additionally, genome editing offers new avenues for the treatment of genetic disorders, potentially transforming the lives of individuals affected by such conditions,” she said.

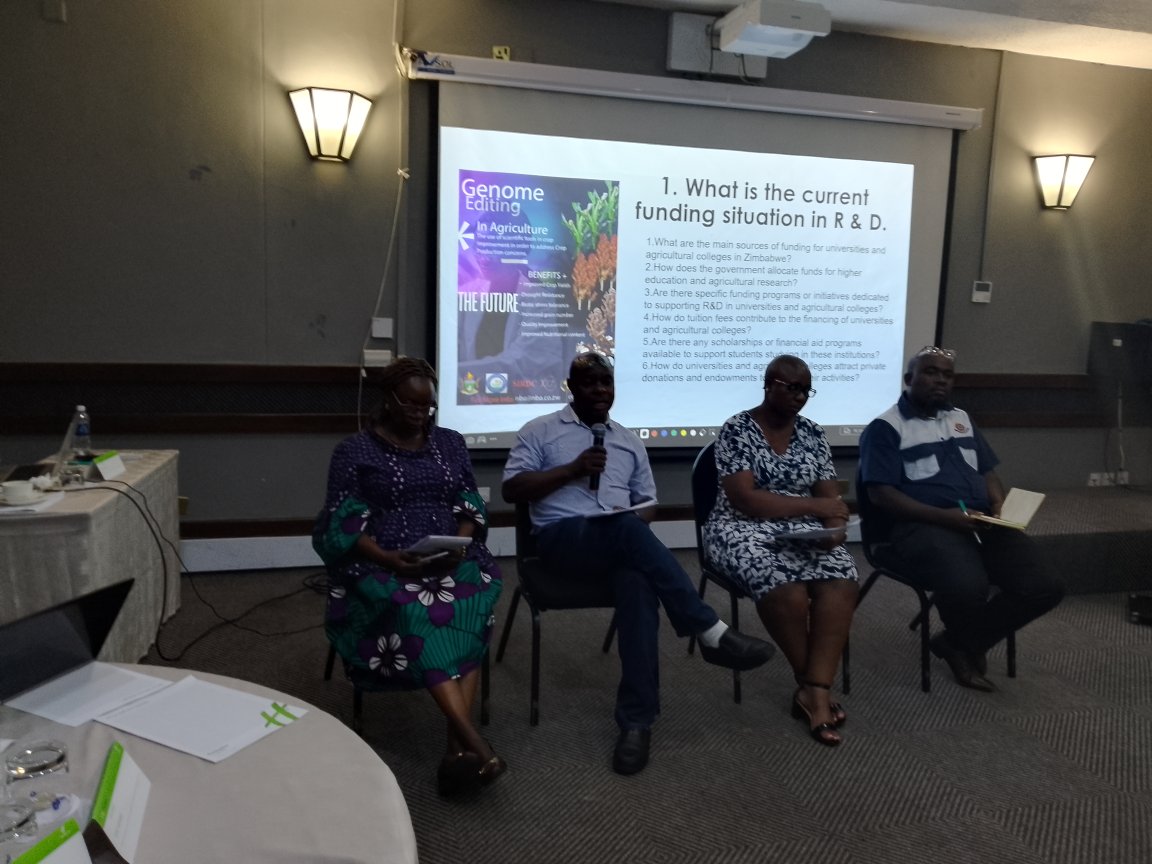

In a panel discussion on the financing of universities and colleges, and support for research and development at a two-day workshop that opened in Harare yesterday that is meant to strengthen institutionalized capacity on genome editing in biotechnology research at institutions of higher learning, Mrs Eleanior Maeresera, a development consultant said African countries have committed themselves to spend 1% of their GDP on research and development, but very few have managed to realize this.

“Funding for research usually comes from the government and is complimented by bilateral and multilateral donors. Banking institutions and philanthropists also play a critical role. Private-sector funding for biotechnology research is limited in Africa,” Mrs Maeresera said.

Dr. Cosmos Magorokosho, the Chief Executive Officer of the Agriculture Research Council (ARC) said there are opportunities for people to approach his institution for project proposals for funding for research.

“We will then approach the government for funding the research. ARC can also give support to put together proposals and then put them to donors. ARC is currently engaging the government to see if there is a policy shift where it can allocate part of the GDP towards scientific research. Working with the government, we are lobbying the private sector so that they can invest in agriculture research and development,” Dr. Magorokosho said.

Dr. Fortunate Makore, a plant breeder lecturer at the Marondera University of Agricultural Science and Technology (MUAST) said state-owned universities are mainly financed by the government to do agricultural research.

“We acknowledge efforts being made towards research but we feel that more can be done. Other players can come in and complement the government. Even research councils should come on board. There is generally limited funding in Zimbabwe. The focus must also be on equipping our laboratories. We should lobby for MOUs with some private sector institutions,” Dr. Makore added.