|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

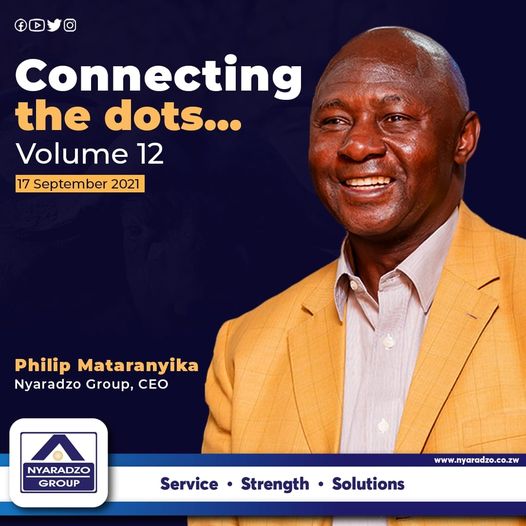

By Philip Mataranyika

When my grandfather Kurauone Kurai Mazikana Mataranyika died tragically in 1940, among the five children he left behind was six-year-old, Steven Tapfumaneyi Mataranyika – my father – who had stayed with our aunt (Tete) Masodzi in Nyatwe, Nyanga, before he was brought back to the village in Gwangwara, along with two other of his siblings. This was after Tongai, his only and elder brother, had fully established himself as a man of means and many talents with capabilities to look after his orphaned siblings.

Were it not for Tete Ziganga, who requested that Tongai stay behind with her when her half-sister, Tete Masodzi, took her late brother’s children into her care in Nyatwe, my father Steven would probably have remained in Nyanga to navigate his own way, perhaps as a herd boy, carpenter, or at best, a subsistence farmer. However, upon his return to Gwangwara, Steven would find himself in unfamiliar territory. The village he came back to had completely changed from the one he had left as a young boy of six in neighbouring Gurure, where his father had met his untimely death due to poisoning, a primitive way of settling petty village jealousies.

As a prince (muchinda) of the royal Makoni dynasty, Kurauone didn’t need to pay much thought about relocating to different places as long as it was within the orbit of Chief Makoni’s rule. Along with his cousin, Julius Mangezi, they had both moved from their familiar surroundings to assert their independence and to pursue their talents kilometres away from their traditional Gwangwara kraal village. While Kurauone opted to settle in Gurure, a neighbouring village, Julius and his family had settled further afield in Chimene, some 15 kilometres north-west of Gwangwara.

Steven’s brother Tongai on the other hand, made his transition to this vastly changed village a lot easier. Tongai had established himself in the village, building a modest house that provided a homely environment when he got married to Laina. His job as a driver – combined with side hustles – were earning him handsome rewards which enabled him to buy a house in the then Salisbury, House Number 2195, Egypt, Highfield.

Tongai had also done the necessary groundwork to ease his siblings into their new environment, as when he made the decision to fetch them from Tete Masodzi in Nyatwe, it was with the blessings of his wife, Laina, who would become the matriarch of the Mataranyika family. She would look after every little soul that needed a mother-figure to lean on, including yours truly when I decided some years later, to return to formal school in the village at Rukweza Secondary School, after years of sweating doing menial jobs while at the same time pursuing distance learning, through what was then popularly referred to as ‘night school’.

At the time, night school had taken root in the nation’s psyche, popularised by adults who wished to advance their education while still maintaining their jobs to earn an income from which they would pay for their school fees. It was also made popular by those whose education had been disrupted by the armed struggle or had missed the opportunity to go to school for various reasons, one of these being the untrusting attitudes that existed at the time towards the education system that had been established by missionaries and our colonial masters. Attending night school would turn heads because most of the students were way past the grades they were pursuing in terms of age. It was therefore not uncommon to see parents being in the same class with their children.

But thanks to the solid footing laid by Tongai, success for his siblings could only be limited by their desires. Just like a bird that first makes a nest before laying eggs, Tongai, together with his wife, Laina, had feathered the family nest for their siblings and many others, who benefited from their tenacity, hard work and generosity, culminating in bringing Tongai’s siblings back to their roots and teaching them to become self-reliant.

Because Steven was his only brother, Tongai did everything he could to toughen him and prepare him for the real world. The ultimate goal for him was to see Steven being able to earn his own keep. Tongai would take his young brother to his house in Egypt, Highfield, so he could learn to drive. Once he was able to drive, Tongai facilitated him securing his first formal job at Clan Transport, initially as an assistant driver, before he assumed the reins, driving his own delivery van. In the evening after work, Steven would go to night school so he could learn to read and write.

In the meantime, Tongai and Steven’s sisters had reached adolescence back in the village, with members of the opposite sex drooling over their amazing and blinding beauty. Their beautiful sister, Sabina, twin to Steven, would attract the attention of Boniface Mukwekwe, a telephone exchange operator, working in Rusape, who wasted no time in paying lobola and organising a white wedding in December 1952 when his heartthrob was only 18. Two years later, on the 28th of September 1954, the couple would welcome their first child, a son, whom they named Michael. The Mukwekwes’ village is in the Makoni area under Kraal-head Mukuwapasi, another of the Gunguwo descendants. The area was quite far back then considering that most travelling was by foot.

Tongai and Steven’s youngest sister, Calista, would follow in the footsteps of her elder sister, getting married to Ephrage Mberi in 1955, before the couple were blessed with their first child, also a boy, on the 15th of July 1956. Ephrage’s village was about 15kms south of Rusape. By the 1960s, Calista and Ephrage’s marriage had been blessed with four children, all boys, Jonah born 15 July 1956, Elijah 11 September 1957, Cephas 13 January 1959, and Patrick Charles 27 October 1960.

The sisters’ changed geographical locations could not diminish Steven’s love towards them. Once he became gainfully employed, Steven would visit them whenever he managed to get some days off. On several occasions while making deliveries from Harare to Mutare, Steven would take a detour to visit each of his sisters on either side of the Harare-Mutare road, risking losing his job. Back then, to have a relative come home by vehicle was such a big deal. It didn’t matter much whether it was a personal or company vehicle, just being behind the wheel was an extraordinary feat.

While Steven’s rags to riches story set tongues wagging in the Gushure village, where Calista, his youngest sister was married, she was worried sick, she thought her brother was running out of time to get married. By now she had four children while Steven was yet to introduce her to his wife to be. Because she thought time was ticking away for her brother to find someone to settle down with and instead of leaving it in God’s hands, she decided to play cupid. At that time, courtships were pre-arranged so it was perfectly normal to have a go-between who played a facilitative role.

Across the Rusape River, towards Tsanzaguru Mountain, from Gushure village where Calista and her husband lived, which is about 15kms South of Rusape, was a village called Bvumbe, so named because it was inhabited and run by the Bvumbe family of the Nyati totem – also descendants of Gunguwo, lived the Musasa family of the Chihwa totem. Samuel Chati Musasa and his wife Jessica, together with their six children had settled there after they were invited by the Bvumbe family into which one of Samuel Chati, my maternal grandfather’s aunties Pindi was married. Among their six children, was a girl named Mabel, whom Calista thought would make a good wife for her brother.

Mabel was the fifth child in her family. Ephrage’s mother and mother-in-law to Calista, was of the Mhofu totem, which was the same as that of Mabel’s mother, Jessica. Totems were very important and key to establishing relationships, then as is now. Strong relationships would be and are still formed just from knowing one’s totem. Once Jessica knew that Ephrage’s mother was a Chihera, she started treating Ephrage as her own son, while Calista became her daughter-in-law (muroora).

Calista had come to know of Mabel as she often visited the Musasa homestead, initially as just another relative, but later as part of a reconnaissance mission to link her up with her brother. Because Calista’s mother-in-law and Mabel’s mother were Chiheras, it was not difficult for Steven’s sister to come visiting the Musasa homestead or for Mabel to cross the river, visiting her sister-in-law and brother. Once she had done her ground work and was satisfied that Mabel was the right candidate to be Steven’s wife, in the year 1961, Calista invited Mabel to come over to their place for an afternoon of relaxing and to catchup.

Mabel accepted the invitation and was given the all-clear by her parents, having probably told them that she was going to have her hair done or something like that to avoid raising suspicion. Upon her arrival at Ephrage and Calista’s residence in Gushure village, she was introduced to this gentleman, Steven, whom Calista said was her brother. Seventeen-year-old Mabel must have been overwhelmed to see this handsome man with a formal job driving Clan Transport delivery vehicles. With so much excitement, the deal must have been sealed there and then, marking the beginning of a courtship that would ultimately lead to the marriage of the lovebirds, later that year. On the 9th of August, 1962, they would welcome their first child, a son whom they named Johannes Mhanamana, named after my father’s uncle, who happened to be my grandfather’s only brother. After they got married, and had moved in together into Steven’s lodgings in Highfield, my father would change jobs, joining the Harare United Omnibus Company (HUOC), which at independence became the Zimbabwe United Passenger Company (ZUPCO).

Tongai’s foresight and big heart would come in handy again. Tongai had extended his four-roomed Highfield house, building an additional two rooms at the back of it, which is where Steven and his wife, Mabel, stayed. I was born almost two years later, on the 26th of March 1964. Revai would follow in 1966, dying in his infancy. A year later, the couple would welcome another child, Thomas – born on the 18th of December 1967. They would also name him Munyaradzi, meaning the comforter.

When Johannes was about to start school, Steven and Mabel reasoned that the best option was for him to go to the village school at Rukweza. The decision meant that my mother had to take the three of us to the village in late 1968. Immediately after we had shifted our base to Rukweza, my father would change jobs to work for the then Umtali United Omnibus Company (UUOC) in Umtali (now Mutare). Our family urban base now became Mutare where we would visit on school holidays, spending time with both our parents. On the 17th of January 1970, we would welcome Donald and on the 28th of January 1972, we welcomed Garikayi. Mother called him Moses, hoping that his coming would mark the beginning of better things to come, given by then, her relationship with father was strained, the reasons for which I will elaborate further.

While working for UUOC, one of the destinations that the father was assigned to was the Mutare-Chipinge route. On one of his many trips to Chipinge, he would get to meet Bertha Mlambo, born on the 2nd of February 1953 – almost twenty years younger than him. It was love at first sight and they started dating almost immediately. Bertha was young and equally overwhelmed about dating a man who drove a bus with a carrying capacity of 75, excluding standing passengers. To turn her head over heels, Steven must have taken Bertha on one or two trips, to and from Mutare, sitting somewhere right behind the driver’s cabin, where his dexterity at driving this big machine would be on display in full view of the enthralled and captivated Bertha. I can imagine the effect it had on a poor girl from a village, deep in Chipinge. I am also convinced that my father must have perfected his art, given that ten years earlier, another woman, Mabel Musasa, my mother, had fallen for the same trick, although my aunt, Calista, had played the biggest part in their courtship.

By 1972, the relationship had blossomed and was the talk of the town, so to speak. It was not long before word about the illicit affair had spread like a veld fire, so much so, that all and sundry knew about it. Bertha was only 19 when my father secretly decided to make her his second wife. On the 6th of August 1972, she would give birth to the couple’s first child, a son whom they named Fungai and on the 24th of December 1974, they would welcome their second child, another boy whom they named Innocent.

At the height of Father’s affair with Bertha, it was obvious to us that something was terribly wrong between our parents as Father was no longer visiting the village that often. The financial tap also dried up as he stopped sending money for the family. My mother had to start scrounging for scraps to keep us fed. The cold war at home took a toll on our schooling given we were used to getting all we wanted during our parents’ happy days.

When it became abundantly clear that my father had lost interest in our upkeep, life became unbearable and our neighbours did not need to be told that my parents union was in trouble. Once again Tongai would come to our rescue, instructing my mother to open an account at a local grocery shop, Kapfumvuti Stores at Rukweza Growth Point, where she would purchase provisions for our upkeep on credit with my uncle pledging to settle the bills at the end of every month. Another financing arrangement was structured for our school fees. To fund the bills, Tongai had to dig even deeper into his coffers given that he had similar arrangements with his wife, Laina (nee Zvomuya), with whom they were blessed with six children namely Chipo Charity, Blessing, Media, Amos, Misheck Dudzai and Farayi Matthew.

Without fail, my uncle would come to the village at the beginning of each school term to settle our bills since his brother was nowhere to be seen. He would also religiously ensure that his account at Kapfumvuti Stores was settled. It must have been difficult for my mother to accept that her husband’s heart had been swept away by a much younger competitor with no prospect of salvaging their marital bliss.

When a relationship loses its spark, often the tragic fallout is that the estranged parents can’t separate their dysfunctional marriage from the welfare of their children. Julius Nyerere summed it up well when he said that “whenever the elephants fight, it’s the grass that suffers”.

In 1973, my father must have come back to his senses as it seemed he wanted to separate the two relationships, that of his failed marriage and that between him and his children. He would hire a car to pick us up from Rukweza during the school holidays of December 1973 so we could stay with him in Mutare. By January 1974, we were attending school at Sakubva Primary School and staying with our stepmother, Bertha. I was enrolled into Grade Four, while my brother, Johannes, was placed in Grade Six at the same school. Thomas, who was seven years old, was enrolled in Grade One. Back then, children would begin their Grade One at seven years of age, unlike the kids of today who start their primary school at six years old, having spent two to three years in Early Childhood Development (ECD).

At the time, Bertha had one child and was expecting their second who arrived in February. To be brutally honest, this period in my life was like hell on earth. Bertha was tough, if not cruel. On many an occasion, for no apparent reason, she would beat us up. What didn’t help our cause was that our mother had unsuccessfully attempted to challenge the status quo when she gate-crashed the party in 1974 as she tried to reclaim what she thought belonged to her.

Her surprise visit torched an ugly fight as the two women traded blows in a bid to assert their rights over their husbands. Unfortunately for us, my father would take Bertha’s side, to the detriment of our mother. Having lost the battle, she would unceremoniously pack her bags – with her tail tucked in between her legs – and decamp to her rural home, leaving us to face the consequences of the fight of the roses.

The years that followed the Hollywood-like drama which played out right before our eyes were horrendous for us. Our stepmother became more vicious and we were subjected to almost daily brutal beatings. Food suddenly became scarce in the house and we quickly adopted coping mechanisms to avoid starving. We would regularly visit relatives who were within walking distance, not that much out of love, but more for survival, through scrounging for food. Three families immediately come to mind, namely Benjamin Mataranyika and his lovely wife, Eubbah in New Dangare, the Marwenzes in Devonshire and Sekuru Samson Musasa and his wife Susan in Zororo.

My father’s cousin, Benjamin Mataranyika and his wife, Eubbah or Mai Lazzie, lived at Number 149 New Dangare. It became one of the places we frequented for respite; Maiguru Mai Lazzie was gracious enough to always provide us with a meal every time we visited, filling our empty stomachs as we were not getting food at home. It became an unwritten rule that each time we came visiting, it was for food, which she so generously provided. Their first son, Lazarus (Lazzie), born a few days after I had been born in March, was my friend and I would always give Bertha the excuse that I had gone to New Dangare to play with my age-mate, which she was still not comfortable with for fear that they may spill the beans, resulting in my father getting to know about the abuse we were being made to endure. With every meal she served us, Maikuru made sure we got a soft drink to go with it. Babamukuru Benjamin worked for United Bottlers and would get weekly allocations of drinks that Maikuru unhesitatingly shared with us at each visit.

My stepmother would literally get away with murder. One day, I was beaten so severely, it resulted in me bleeding profusely and getting swollen. When the time came that Father would be home, I was instructed to go to bed early and pretend as if I was fast asleep. I was also warned that if my father got to know about the beatings, it was either I was to be thrown out of the house or there wasn’t going to be any peace. For fear of further persecution, I obeyed her command and my father never got to know about it.

To avoid becoming a nuisance at 149 New Dangare, we would also visit my mother’s brother, Samson and his family, for food in Zororo, house number 326. Samson and his wife Susan whom we called, Mbuya Mai Edward, would treat us like royalty and feed us well before we went back home to sleep.

Back home, there would be some food left for us on the odd occasion, but mostly there was nothing and if any, it was of such poor quality, one would eat only when they were really hungry. My stepmother had an unwritten rule which applied to my brothers and I, especially when my father was away on duty in that she wouldn’t provide any food for us because her assumption was that whoever was hosting us should have fed us as well. The list of offences that were punishable by beating was as long as the original snake. I was usually the culprit, as I was hyper-active and as a result, I was on the receiving end of most of the punishments meted out.

If we were not at home, in New Dangare or Zororo, you would certainly find us at the house of Peter Marwenze, (Murahwa) of the Shumba totem who worked for the Rhodesia Railways (RR), now National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ), one of the most esteemed and prosperous Parastatals of the time. He was the son of Mwadini, sister to my maternal grandfather Samuel and nephew to my mother Mabel.

Peter lived in Devonshire, a suburb that housed RR workers with his wife, Maiguru and their children, Itai a.k.a Jethro, Joyce, Maxwell, Mavis, Godfrey, Judith, Viola, Cecilia and Collen. The whole family received us well each time we went visiting, treating us to sumptuous meals.

I am forever grateful to these three families who literally saved our skins when our chips were really down.

A year later, we were back on the road again, this time heading for Harare, back to where it all started, at Number 2195 Egypt, Highfield. This was after my father had changed jobs once again at the end of 1974, re-joining HUOC. In 1975, we would start school at Tsungai Primary School in Highfield.

The prospect of being subjected to the ongoing abuse and now being far away from the three families that had hitherto been coming to our aid would send shivers down our spines. At the time of moving to Harare, my little brain was troubled. Foremost on my mind was the fact that the safety nets we had built in Mutare were staying behind while we moved, we didn’t know anyone on whom we could rely for food in case we weren’t fed because my uncle Tongai’s family had moved to the village in Rukweza. Secondly, we didn’t know if any new source we were to identify for supplementary (which in reality would be pretty much the main source of food) would be discreet enough so as to avoid letting our little secret out to Mainini Bertha.

As fate would have it, we would find a new reliable source of food in neighbouring Lusaka. Tete Diana – a niece to my mother, daughter of Rena, another of my maternal grandfather Samuel’s sisters, became our guardian angel, providing us with food when we went hungry. For most of early 1975, we would go visiting at her home, coming back well fed.

Around mid-1975, Mainini Bertha decided to start a vending business, specialising in selling oranges. She would buy oranges from Mazowe Valley which she would give us to sell during the weekend when we were not at school. This gave us a good reason to be away from home as we were doing chores, assigned to us by her.

I would soon identify a big market for the oranges. Back in the day, there were only two stadiums in the ghetto namely Rufaro Stadium which had been officially opened in September 1972 by the colonial city fathers, and Gwanzura Stadium which had been built in the 1960s by brothers Eric and Fanuel Gwanzura to defy colonial restrictions on access to sporting infrastructure for black Africans.

On account of its proximity to our home, I would focus on Gwanzura Stadium which was the home for most big clubs in then Salisbury. As an orange vendor, I attended almost all the matches played at the 10,000 seater facility in 1975/76, excelling at the trade, selling almost all the oranges I was allocated every Saturday and Sunday. On many occasions after running out of stock, I would use the day’s takings to buy from other vendors who would be struggling to sell, add on a small margin, and generate a few dollars more on the side.

With time, Mainini Bertha would pay a small commission to encourage us to sell more. Once we were running errands for her, the conditions at home improved, food was provided and the quality thereof became better, alleviating the need for us to go around scrounging for food.

I struggled at school, getting poor grades in a class with sharp shooters, amongst them Godfrey Mubaiwa, who was our neighbour, Emmanuel Mudavanhu – another smart guy who also stayed a few houses from ours. Fancisca Nhau, sister to Albert Nhau, who was the tallest in our class, was also my classmate, so were brothers Tichaona and Boyd Kembo, as was Edward Nyandebvu, also a neighbour in the same line. Unfortunately, Edward would develop mental illness immediately after finishing Grade Seven, that afflicts him up to this day, my heart bleeds for him, but boy, oh boy, was he a good soccer player. Godfrey was also a good soccer player as were his two brothers, Elvis and Kennedy, who would make all of us proud when he qualified as a medical doctor, years later.

Because I didn’t consider school that important at the time, I joined a delinquent group of naughty lads who included John Chidyiwa and Shepherd Murombedzi. Together we would be all over doing our mischief thing, coming home late sometimes, to the chagrin of my stepmother. Tsungai Primary School was a few minutes away from home. I would literally run to school shortly before the assembly bell and still be on time for class.

For the two years I was at Tsungai, my teacher was Mr James Chiripamberi, of the Shumba totem, whom I would get to know – long after I had left school – as my homeboy from across our village in Gurure where my grandfather, Kurauone Kurai Mazikana had relocated to and died way back in 1940. His daughter, Esnath Ethel (now Svondo), would be one of my very good friends after we left school and we remain so up to this day.

For the greater part of 1976, life at home was no longer as brutal as it was before. Perhaps it was because Mainini Bertha, at 23 years-old, was now more mature and reasonable, or perhaps it was because Father no longer found her attractive and she felt bad for the way she had treated us for the previous two forgettable years and therefore needed our sympathy.

One late afternoon in December, we would come back home from school to find Mainini Bertha gone, taking her two sons, four-year-old Fungai and two-year-old Innocent with her. Her departure coincided with the start of the December school holiday. At that point, it became clear that our step-mother probably thought she had sold herself short by getting married to a “mere driver” who was 20 years her senior. While we were left guessing her motives for turning her back on Father, word in the neighbourhood was that she must have been looking for greener pastures all along.

Once Mother got to hear about Bertha’s departure, she would negotiate for the custody of us children, which Father didn’t object to, resulting in us moving in with our mother to Chitungwiza, where she was staying in Unit A, Seke, otherwise known as House Number 1693.

Nonetheless, this wasn’t our last dance with our father. Even though my stepmother’s departure could not rekindle the flame between our parents, our father remained part of our lives right up to the time of his death. Whenever he was around, which was not often, we felt loved and protected, in his absence, we felt vulnerable. However, we were privileged to have a huge support structure in the form of our extended family that came to our rescue, without which I can’t even start to imagine how bad and miserable our lives would have turned out to be. My life and that of my siblings is living testimony of and evidence to the wise words of our African sages who said, ‘it takes the whole village to raise a child’.