By Brian Raftopoulos

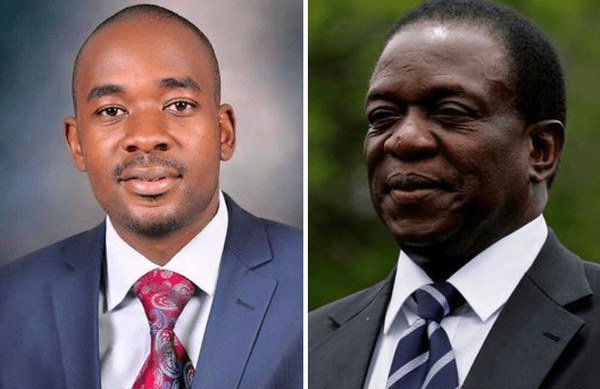

Since the November 2017 coup that toppled Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and the elections in 2018, the regime of President Emmerson Mnangagwa has forged two forms of rule. These have been based on coercion on the one hand, and on the other dialogue.

Following the 2018 general elections and the violence that marked its aftermath, the Mnangagwa regime once again resorted to coercion in the face of the protests in January 2019. The protests were in response to the deepening economic crisis in the country, and part of the opposition strategy to contest the legitimacy of the government.

The response of the state to the protests was swift and brutal. Seventeen people were killed and 954 jailed nationwide. In May the state turned its attention to civic leaders, arresting seven for “subverting” a constitutional government. The repressive state response was felt once again on 16 and 19 August, when the main opposition Movement for Democratic Chance (MDC) and civic activists were once again prevented from marching against the rapid deterioration of Zimbabwe’s economy.

These coercive acts represent a continuation of the violence and brutality of the Mugabe era.

At the same time Mnangagwa has pursued his objective of global re-engagement and selective national dialogue. This is in line with the narrative that has characterised the post-coup regime.

In tracking the dialogue strategy of the Mnangagwa government, it is apparent that it was no accident that key elements of it were set in motion in the same period as the agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on a new staff monitored programme.

The purported objective is to move the Zimbabwe Government towards an economic stabilisation programme. This would result in a more balanced budget, in a context in which excessive printing of money, rampant issuing of treasury bills and high inflation, were the hallmarks of Mugabe’s economic policies.

The dialogue initiatives also took place in the context of renewed discussions on re-engagement with the European Union (EU) in June this year.

But, Mnangagwa’s strategy of coercion and dialogue has hit a series of hurdles. These include the continued opposition by the MDC. Another is the on-going scepticism of the international players about the regime’s so-called reformist narrative.

Dialogues

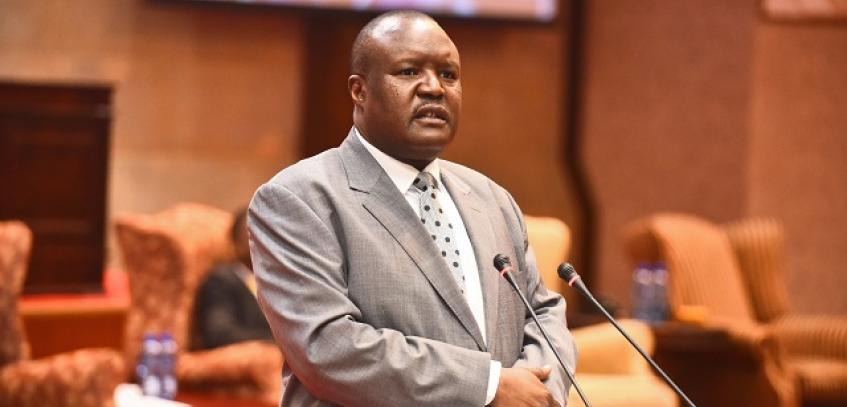

Mnangagwa has launched four dialogue initiatives.

- Political Actors: This involves about 17 political parties that participated in the 2018 elections. They all have negligible electoral support and are not represented in parliament. The purported intent is to build a national political consensus. The main opposition party, the MDC, boycotted the dialogue, dismissing it as a public relations exercise controlled by the ruling Zanu-PF.

- The Presidential Advisory Council: This was established in January to provide ideas and suggestions on key reforms and measures needed to improve the investment and business climate for economic recovery. This body is largely composed of Mnangagwa allies.

- The Matabeleland Collective: This is aimed at building consensus and an effective social movement in Matabeleland to influence national and regional policy in support of healing, peace and reconciliation in this region. But it has come in for some criticisms. One is that it has been drawn into Mnangagwa’s attempt to control the narrative around the Gukurahundi massacres. These claimed an estimated 20 000 victims in the Matabeleland and Midlands regions in the early 1980’s. Another criticism is that it has exacerbated the divisions within an already weakened civic movement by regionalising what should be viewed as the national issue of the Gukurahundi state violence.

- The Tripartite National Forum: This was launched in June, 20 years after it was first suggested by the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions. The functions of this body set out in an Act of Parliament, include the requirement to consult and negotiate over social and economic issues and submit recommendations to Cabinet; negotiate a social contract; and generate and promote a shared national socio-economic vision. The establishment of the forum could provide a good platform for debate and consensus. But there are dangers. The Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions warned of the long history of the lack of “broad based consultation on past development programmes”. It insists that “reforms must never be deemed as tantamount to erosion of workers’ rights.”

The strategy

In assessing the central objectives of the various strands of Mnangagwa’s dialogue strategy, three factors stand out.

The first is that the Political Actors Dialogue, the Presidential Advisory Council and the Matabeleland Collective were developed to control the pace and narrative around the process of partnership with those players considered “reliable”. Major opposition and civic forces that continued to question the legitimacy of the Mnangagwa boycotted these processes.

Secondly, the formal establishment of the long awaited Tripartite National Forum may serve the purpose of locking the MDC’s major political ally, the Zimbabwe Council of Trade Unions, into a legally constructed economic consensus. The major parameters of this will likely be determined by the macro-economic stabalisation framework of the IMF programme.

When brought together, all these processes place increased pressure on the political opposition to move towards an acceptance of the legitimacy of the Mnangagwa regime, and into a new political consensus dominated by the ruling Zanu-PF’s political and military forces, thus earning them the seal of approval by major international forces.

The MDC has responded with a combined strategy of denying Mnangagwa legitimacy, protests as well as calls for continued global and regional pressure. The MDC believes that the continued decline of the economy will eventually end the dominance of the Mnangagwa regime.

As part of its 2018 election campaign, the MDC made it clear it would accept no other result than a victory for itself and Chamisa. That message has persisted and is a central part of the de-legitimation discourse of the opposition and many civic organisations. The MDC has regularly threatened protests since 2018.

What next

The MDCs strategies have not resulted in any significant progress. The hope that the economic crisis and attempts at mass protests to force Zanu-PF into a dialogue are, for the moment, likely to be met with growing repression. Moreover, the deepening economic crisis is likely to further thwart attempts to mobilise on a mass basis.

The EU, for its part, is still keen on finding a more substantive basis for increased re-engagement with Mnangagwa and will keep the door open. Regarding the US, given the toxic politics of the Trump administration at a global level, and the ongoing strictures of the US on the Zimbabwe government have contributed once again to a closing of ranks around a fellow liberation movement in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region.

Mnangagwa’s recent appointment as Chair of the SADC Troika on Politics, Peace and Security in Tanzania will only further cement this solidarity.

There is clearly a strong need for a national dialogue between the major political players in Zimbabwean politics. But there is little sign that this will proceed. Moreover, the current position of regional players means that there is unlikely to be any sustained regional pressure for such talks in the near future.

Source: The Conversation

Brian Raftopoulous is a research fellow at the International Studies Group, University of the Free State