|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Charles Dhewa

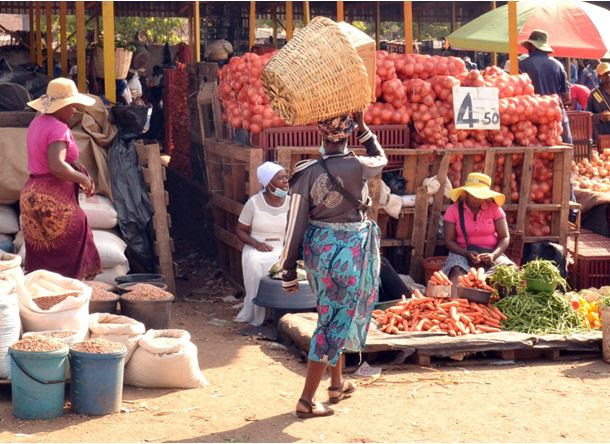

That most African economies have two different economies – formal and informal- is no longer debatable. Besides supporting the formal economy, during shocks like COVID19, the informal economy has become a source of resilience for the majority of farmers, vendors, traders, and low-income consumers. The same applies during drought periods when formal companies feel the heat more than informal enterprises.

Tying two different solutions

For almost all African countries including Zimbabwe, when there is an economic crisis that forces the price of food upwards, the formal economy resorts to salary increments so that consumers can be able to buy food. But that is not a solution in informal economies where the majority do not receive monthly salaries. The informal economy is not more about salaries but focuses on leveraging appropriate support that can expand informal enterprises. For instance, with respect to food systems, attention can be on reducing food supply-related costs as well as strengthening aggregation and supply systems. Addressing such challenges reduces the landing cost of food, making it affordable for the majority of consumers, not just those who receive monthly salaries.

For most developing countries, more important than increasing salaries of consumers is building strong food distribution systems from production zones to consumers and processors. Designing efficient food distribution systems may not require investment in new infrastructure or foreign currency. It may only require thoughtful and creative positioning of actors within food systems and supply chains in ways that reduce redundancy. Without proper position of actors within food systems, countries that depend on few exports like cocoa, cotton, and tobacco will have incomes from these commodities eroded by the high cost of food.

Taking a cue from African mass food markets

Unique values have enabled the African food market to survive for centuries and out-live some formal markets. For instance, African markets recognize the fact that, by nature, people belong to different religions and political parties but when it comes to providing food to the population or serving in their sector, politics, and religion have no role. External values are not allowed to interfere with the business of trading food commodities. Another key lesson is that these institutions have salient governance structures that consumers who walk in and out of the market may not know to exist. All actors are galvanized by a strong need to address the same objective of earning a living.

Local solutions are sought for any issues or challenges that emerge within or outside the markets. For instance, if security is weak, traders and other actors make their own contributions to set up their own security system. When traders are excluded from formal finance systems, they come up with their own credit models like Mukando or stokvels. Where formal medical or funeral services become unaffordable, traders pool resources toward creating their own solutions.

In most markets, during the time COVID19 was at its peak, market traders were coming to the market in turns in order to avoid crowding and contributed toward buying their sanitizers. More importantly, African food markets do not use politics to discriminate commodities that come to the market. This is contrary to formal markets at the national level where countries struggle to get into export markets due to politically-inclined sanctions or related measures.