|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

South Africa must redouble its efforts to tackle the crude legacy of pre-1994 environmental racism, including the abhorrent practice of intentionally situating landfills and polluting industries along racial lines and in low-income and migrant communities, a UN expert said today.

“To this day, the legacy of pervasive air, water, and chemical pollution disproportionately impacts marginalised and poor communities,” said Marcos Orellana, the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights in a statement issued at the end of an official visit to South Africa.

“The challenges to overcoming the legacy of environmental racism are enormous, and they are compounded by structural inequality, widespread poverty, unemployment, and new environmental threats such as hazardous synthetic chemicals and the climate emergency,” Orellana said.

The Special Rapporteur noted that the South African Constitution is renowned worldwide for its advanced positions on human rights. For example, the Constitution recognises the justiciable right of everyone to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being. He pointed out that it took the UN General Assembly another 25 years to globally recognise the critical importance of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.

Since 1994, South Africa has also adopted important norms governing chemicals and wastes. There are also important measures in progress, such as a project to eliminate polychlorinated biphenyls, a program to remove asbestos from roofing, and a climate bill.

“But at the same time, there are laws predating 1994 that continue to result in harms and human rights infringements, such as the laws governing hazardous waste from 1973 and pesticides from 1947,” Orellana said.

“South Africa’s strong legislative framework should serve as the backbone for accountability and access to effective remedies,” he said. “Yet where powerful actors are allowed to act with impunity and disregard environmental protections, the confidence in democracy and the environmental rule of law begin to erode.”

According to the expert, for many decades, the mining industry has contributed to South Africa’s economic development. Its legacy also includes thousands of derelict mines and mine waste dumps in the country. Orellana said that often, the hope for pollution prevention and remediation upon mine closures is lost in the poor enforcement of legislation. “The result is a landscape scarred by abandoned mines, tailing dumps, and acid mine drainage,” he said.

Dust from coal mines, along with ashes, mercury emissions, and PM2.5 from coal burning have a severe negative impact on air quality, as the country generates almost 90% of its electricity from coal. South Africa has begun to transition away from fossil fuels for energy production, but the process faces serious obstacles, not least the licensing of new coal mines and offshore oil and gas, the expert said.

“In the Western Cape province, I heard from women farm workers who were routinely exposed to hazardous pesticides and who denounced serious adverse health impacts in their communities,” Orellana said. The expert said that during his visit he had also learned that pesticides meant for agricultural use are illegally sold and used to combat rampant rat and cockroach pest infestations that spread in the absence of sanitation and waste management services in informal settlements.

“I was appalled to learn of the many children who were poisoned or died from eating, drinking or handling hazardous pesticides,” Orellana said. “South Africa should ban the import of all highly hazardous pesticides, including those that have been banned for use in their country of origin, without delay,” he said.

At the conclusion of his visit, the Special Rapporteur thanked the people of South Africa for their hospitality and the Government for its invitation to visit the country. The UN expert will present a report on his visit, including his findings and recommendations to the Human Rights Council in September 2024.

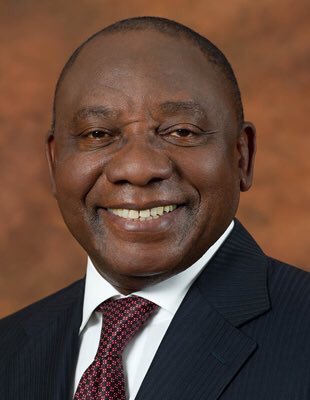

Marcos A. Orellana, Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes, was appointed by the Human Rights Council in July 2020. Dr. Orellana is an expert in international law and the law on human rights and the environment.

His practice as a legal advisor has included work with United Nations agencies, governments, and non-governmental organizations, including on wastes and chemicals issues at the Basel and Minamata conventions, the UN Environment Assembly, and the Human Rights Council. He has intervened in cases before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, and the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body.

His practice in the climate space includes representing the eight-nations Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean in the negotiations of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and serving as senior legal advisor to the Presidency of the 25th Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

He has extensive experience working with civil society around the world on issues concerning global environmental justice. He was the inaugural director of the Environment and Human Rights Division at Human Rights Watch. Previously he directed the trade and human rights programs at the Center for International Environmental Law, and he co-chaired the UN Environment Program’s civil society forum. He teaches International Environmental Law at the George Washington University School of Law and International Law at the American University Washington College of Law.

Previously he has lectured at prominent universities around the world, including Melbourne, Pretoria, Geneva, and Guadalajara. He was a fellow at the University of Cambridge, visiting scholar with the Environmental Law Institute in Washington DC, and an instructor professor of international law at the Universidad de Talca, Chile. The Special Rapporteurs are part of what is known as the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council.

The Special Procedures, the largest body of independent experts in the UN human rights system, is the general name for the Council’s independent investigative and monitoring mechanisms that deal with specific country situations or thematic issues in all parts of the world. Special Procedures experts work on a voluntary basis; they are not UN staff and do not receive a salary for their work. They are independent of any government or organisation and serve in their individual capacity.

UN Human Rights, country page – South Africa