By Sue Edmonds

What is really under our feet these days? Is there still any life down there?

I still remember a field day I was covering some years ago, where the featured expert stood in the field and asked a goodly crowd of farmers what they thought they were standing on. There was a lot of nervous viewing of feet, and one or two ventured ‘loam?’

Nobody appeared to have a clue about the trillions of soil life –mycorrhizae and their glomalin, numberless bacteria, good and bad nematodes and all those necessary minerals being exuded and taken up symbiotically by those below and the green things on top.

There is this curiously (may I say it?) masculine idea that we are such whizzes at technology these days that we have the world, and its productivity, sorted. That guy Justus von Liebig sorted out in about 1840 which chemical elements were needed to make plants grow, and we’ve been spreading them liberally ever since we worked out how to create them in quantity.

In recent years I have read an enormous amount about something needing to happen in the soil to make those chemicals acceptable to plants, and very little about what was already present down there which could be dragged up from the depths by that soil life, changed by them, and then presented to plants with the right flavours and qualities.

And the dosages we’ve spread of those chemicals over time have discouraged that soil life from even trying, so it dies off or moves away. Many farmers are aware that clovers, which used to make all the plant available nitrogen needed in their little rhizomes, simply found they weren’t needed and gave up doing so. And along came a root weevil who found inert roots with no rhizomes, and munched happily on any that was left.

Has it never occurred to many that the bug infestations which we get regularly these days could have something to do with the fact that the particular types of soil life which used to deter them, and prevent massive multiplication, are simply not there any more?

There are already places in the world where so many chemicals have been applied that absolutely nothing green will grow there now. We have already moved from applying 55,000 tonnes of urea in the 1980s to around 700,000 tonnes last year. I haven’t noticed reports that our country has grown 12 times bigger in that time!

So, what do we need to do? We need to ‘regenerate’ our soils by studying what Nature does at different times of the year, reduce our chemical inputs, possibly add some carefully bred mycorrhizae and bacteria and let them multiply and start doing their proper job.

We need to stop ploughing before and after our crops. We need to make sure that bare soil is covered with plant material at all times if possible (Nature and soil life don’t ‘do bare’.) We need to plant multiple species both in cropland and pasture, and let each do what it’s good at, again symbiotically.

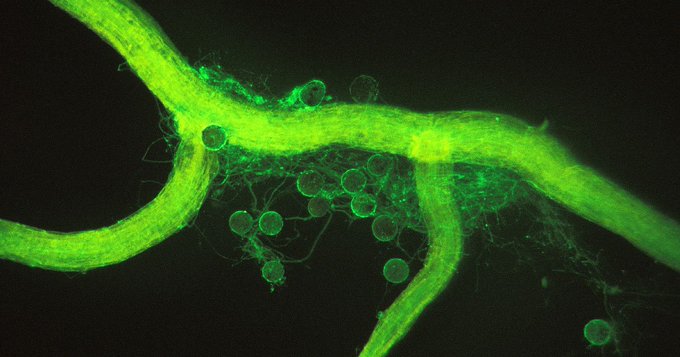

And what will all of this achieve? Well when the mycorrhizae put out their miles long hyphae and the lovely sticky glomalin coats each strand, we shall get agglomeration of all those tiny dirt particles, creating small pure spaces for both air and to hold water when it rains. We shall make use of the enormous amount of phosphate we’ve added over the years, which currently either runs off during rain, or just sits and sulks because it’s the wrong formula for plants. The more than 60% of what we spread will stop sifting down into groundwater and messing up our streams and rivers.

And best of all, when the soil life gets going we shall grow more of everything, and that growth will have a high nutritive value. And all those poor cows and sheep, whose tummies get upset by the urea on and in the pasture, won’t have to burp and drink and pee madly to cope with their rumbles which it currently causes. And think what that might do for our climate change efforts.

This is the second in a series of articles by Sue Edmonds on regenerative farming with more to come. New ideas and systems are always difficult to absorb quickly, and we shall look at different aspects of what has already occurred and what different thinking might need to be done.